By John B. Dower

This article is a follow-up to one that appeared in the Cocumscussoc Review one year ago and is an example of the ongoing research taking place at Smith's Castle. The author further investigates a statement by Rhode Island founder Roger Williams concerning Richard Smith Sr. and his “servants.” The words of Roger Williams are further evidence of enslaved people, most likely of African descent, being with the Smiths at Cocumscussoc before 1650.

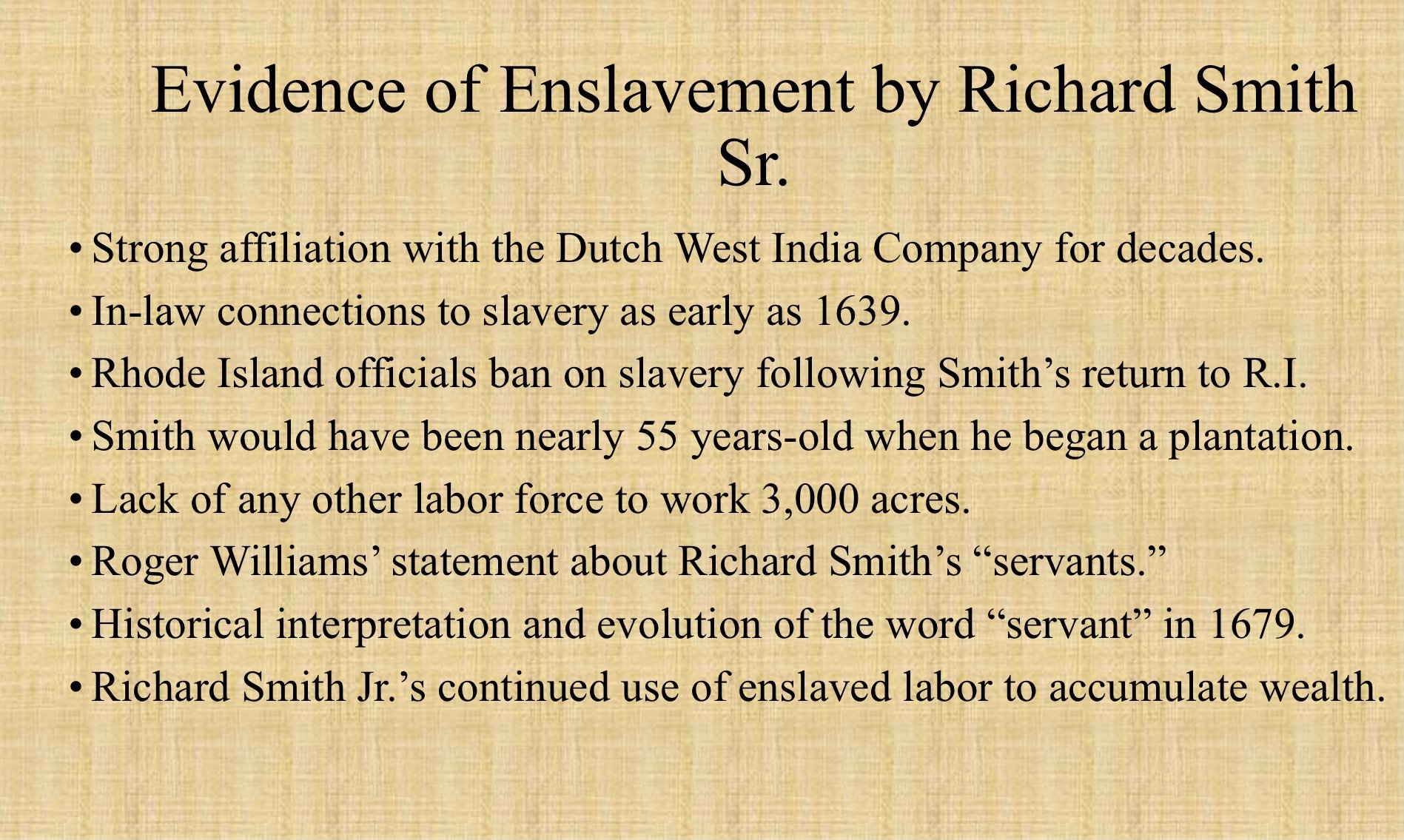

For well over one hundred years, slavery took place at the great plantation house at Cocumscussoc. In fact, the Smiths and Updikes may have enslaved people of color for a period that lasted over one hundred and fifty years, which would have preceded the infamous slave voyages out of Rhode Island by several decades. While the Smiths and Updikes from Cocumscussoc were not known to have been direct participants in the notorious voyages that departed from Newport and Bristol in the eighteenth century and brought thousands of enslaved Africans to the Americas, they certainly were involved with the slave trade on a more personal level at the first plantation in Narragansett Country. The Smiths were early players in what would eventually become the Triangle Trade, first with Richard Smith Sr.'s involvement with Dutch trade and the Dutch West India Company, and later when Richard Jr. sent his own ship to Barbados. Some forty known people, mostly of African descent or mixed race, were held in bondage at Smith's Castle for a period that began in the 17thcentury and did not end until the 19th century. That number of forty enslaved is likely much higher than what has been gleaned from the scant number of documents existing on the Cocumscussoc Plantation.

We know with certainty that a minimum of eight enslaved people had lived and toiled at Smith’s Castle by 1692. Richard Smith Jr.’s will from that year lists eight people held in bondage, three adults and five children. While no documentation has been found that specifies a date for the first arrival of enslaved people at Smith’s Castle, evidence points as far back as the early 1650s, and perhaps before, when Richard Smith Sr. made Cocumscussoc his permanent residence. The elder Smith returned to his immense landholdings when trade in beaver pelts was in decline. His business focus turned to livestock and cheese production, which would have required the necessary workforce that enslaved people could only provide. No doubt, Rhode Island’s officials had witnessed the enterprise of these Englishmen beginning to emulate Dutch plantation practices at Cocumscussoc. Curiously, the colony of Rhode Island banned the practice of lifetime slavery in 1652 when the lawmakers met just up the road in Warwick. The law read as follows-

“Wheras, it is a common course practiced amongst English men to buy negers, to that end they have them for service or slave forever: let it be ordered, no black mankind or white being forced by covenant bond, or otherwise, to serve any man or his assighnes longer than ten years…And at the end or terme of ten years to sett them free, as the manner is with English servants.”

The failed 1652 law enacted in Rhode Island is an early indication that workers held "for service" were sometimes being forced into lifetime bondage by the middle of the seventeenth century. But, for the most part, that law was ignored, and much of the disregard took place in Narragansett Country.[i]

It is probably not a mere coincidence that at the same time, Rhode Island officials attempted to prohibit lifetime servitude in 1652, they also drafted another piece of legislation that could only be associated with the Smiths-

“Ordered, that all Dutchmen, except inhabitants amongst us, are prohibited to trade with the Indians in this Collonie…”

Undoubtedly, Rhode Island leaders were vitally aware of Richard Smith's permanent residence in New Amsterdam and his close affiliation with the Dutch West India Company. Although the Dutch had at various times before 1652 attempted to establish trade in Rhode Island with the Narragansett people, Richard Smith was the most influential person in the colony that was involved with the Dutch by 1652. Unfortunately, friction between the English and the Dutch would only worsen in the next decade, and the Smiths' permanent presence at Cocumscussoc set off more than a few alarms.[ii]

The most substantial proof of Richard Smith Sr.’s use of enslaved labor at Cocumscussoc can be found in the words of Rhode Island founder Roger Williams. When testifying over a land dispute involving the younger Smith in 1679, Williams described the elder Smith during the years before making Cocumscussoc his permanent residence-

“…about forty years ago from this date, he kept possession, coming and going himself, children, and servants, and he had quiet possession of his houses, lands, and meadows…”[iii]

Roger Williams, founder of Rhode Island and long-time associate of the Smith family.

The use of the word servant before the mid-1600s would have been associated most commonly with the indentured servitude of people of any race that were held for an often-specified term. Records of Rhode Island's lawmakers from 1647 and 1649 describe "servant" as associated with words such as “termes” and “a term covenanted.” There was even a belief early on among some enslavers of Africans that it would be a temporary period for which they held their servants, much like indentured servitude. The 1652 act banning lifetime service is where we can begin to see the definition of "servant" start to become complicated. And the lawmakers knew it. A decade later, the word "servant" was used in Rhode Island's official records to describe people as property. In a situation in 1669 where a man was accused of harboring some runaways, we find the phrase, "hee kept six servants belonging to [another] man."[iv]

By 1679, the word servant had unmistakably evolved to include those permanently enslaved. In a law designed to prevent anyone in the colony from performing labor on the Sabbath, Rhode Island officials sought to fine those “evill minded” men that “requireth, their servants…to labor on the first day of the week.” This was a law and language that Roger Williams would have, no doubt, been familiar. It is also important to note that the word servant in 1679 was used contemporaneously to mean a “person serving a master or lord.” To tie the justification of slavery to religious interpretation, white slaveholders avoided using the word slavery. Instead, they suggested that much like bondservants referenced in the Bible, enslaved Africans were merely serving their white masters. It was hoped this “middle ground” of lifetime servitude of African "servants" would appease those who opposed slavery, and it worked.[v]

Records describing Africans held in bondage in New England during the latter half of the seventeenth century almost exclusively used the word "servant" rather than "slave." This practice is confirmed in the Records of the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations. A piece of legislation passed in 1695 demonstrates how imbued the word "servant" had become in describing the enslaved. For taxation purposes, Rhode Island lawmakers sought to determine "every man's rateable estate,” which meant placing a value on not just livestock but also enslaved workers. As the act read, “for negro servants and cattle, we set these certain prices.” “Negro men servants” were given a value of 18 pence, “negro women servants” 10 pence, and steers and cows 2 pence per head.[vi]

During the time that Richard Smith Sr. was "coming and going" between Cocumscussoc and New Amsterdam, he would have had considerable access to African "servants" due to his strong association with the Dutch West India Company. The Dutch had brought thousands of enslaved Africans to the colonies by way of the West Indies before 1650. The possibility that any of the Smith’s “servants” were indentured Indigenous people or whites when the Smith family lived in New Amsterdam is highly remote, as the rationale for the importation of Africans to the colony was the near total lack of any local labor force. In 1679, Roger Williams would have been quite familiar with the terminology of the time as he described the people working at Cocumscussoc. The logical conclusion of Roger Williams’ 1679 testimony, where he describes Richard Smith's "servants," when taken in the light of the 1652 law, is that Richard Smith utilized enslaved labor sometime before 1650.[vii]

Certainly, Richard Smith Junior became one of the wealthiest men in New England following his father’s death by utilizing enslaved labor. However, that didn't happen overnight. The three enslaved adults listed in his will had, no doubt, been at Smith's Castle for some duration before Junior's death in 1692. The strong possibility also exists that other enslaved people had come and gone in the decades between the deaths of the two Smiths. In his will, it had been the younger Smith’s wishes to manumit two of the three adults upon his death, something not likely to occur unless they had been working on the plantation for many years and developed a personal relationship of sorts with their master. By that point, Junior's nephew, and heir to the plantation, Lodowick Updike, was already in control of a portion of the estate left to him by his grandfather, Richard Smith Sr. The Updike family’s involvement in slavery dates back to 1639, making it very possible that Lodowick, like his father Gysbert, was already involved in the practice before his uncle's death in 1692.[viii]

Like his grandfather, Richard Smith Sr., little documentation survives telling the story of the slavery that existed in the household of Lodowick Updike and his wife (and first cousin) Abigail. All that survives from a fire that destroyed North Kingstown records is a portion of Lodowick's will identifying one enslaved woman, "Penny," and a mysterious comment that mentions "others."

We know that Lodowick’s uncle, Richard Smith Jr., left him five enslaved young people upon his death. It is also possible that, in addition to those five, Lodowick had his own workforce at the time he inherited property from Richard Smith Sr. in 1666. What transpired on the Cocumscussoc Plantation between 1692 and 1737 regarding enslaved people will most likely remain a mystery.[ix]

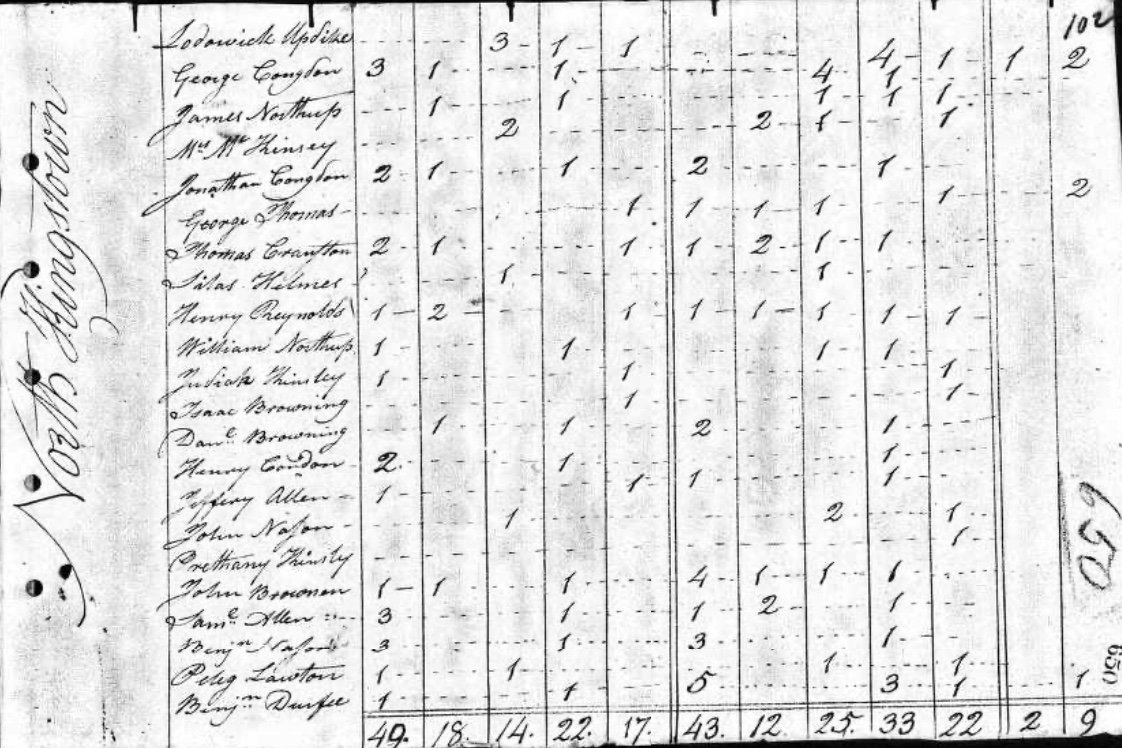

It is the next two generations of Updikes where we have clear documentation concerning the number of enslaved people residing at Smith's Castle. Daniel Updike's will in 1757 lists nineteen enslaved people, only one unnamed. Daniel’s son, Lodowick, is listed as the head of the household in a 1774 census, which lists eleven people as Black out of a total of twenty-two people living at the Cocumscussoc Plantation. While slavery had already been in decline in New England before the American Revolution, many more enslaved people had likely lived at the Cocumscussoc Plantation in the middle of the eighteenth century. A nearby cemetery for the enslaved was known to be the final resting place for eighty-one souls and possibly dozens more.[x]

The last time enslaved people lived at Smith’s Castle would appear to be the decade after 1800. The 1800 Federal Census lists two enslaved people in the household of Lodowick Updike. That would bring a close to what now appears to be over a century-and-a-half of slavery at Cocumscussoc that began with the immigrant Richard Smith.[xi]

The 1800 Federal Census showing two enslaved people residing in the household of Lodowick Updike.

When the first of the infamous slave voyages began to depart from Newport and Bristol in 1700, slavery had become firmly entrenched in the smallest British Colony in North America. At least a half-century before, an Englishman with connections to the Dutch slave trade had introduced his own "servants" to Rhode Island. The Narragansett Country, as well as the lives of perhaps thousands of people of African and Indigenous ancestry, would be forever changed.

[i] Opdyck, Charles Wilson and Opdyck, Leonard Ekstein, The Op Dyck Geneology, p. 82. Rhode Island and Russell, J. Bartlett, Records of the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations in New England, v 1, p.243.

[ii] Rhode Island, v 1, p. 243. Landrigan, Leslie, “The Dutch in New England: More Than Sinterklaas and Koekjes,” New England Historical Society, https://newenglandhistoricalsociety.com/the-dutch-in-new-england-more-than-sinterklaas-and-koekjes/

[iii] Opdyck, p. 78.

[iv] Rhode Island, v 1, pp. 177, 182.

[v] Rhode Island, v 3, pp. 30-31. Fischer, David Hackett, African Founders, pp. 55-56. “Servant,” Merriam-Webster.com,https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/servant.

[vi] Greene. Lorenzo J., The Negro in Colonial New England 1620-1776, p. 290. Rhode Island, v 3, p. 308.

[vii] McManus, Edgar J., A History of Negro Slavery in New York, p.4.

[viii] A review of over 18,000 probate records from UCDavis found at https://gpih.ucdavis.edu/files/Main_Main_New_Eng_probates_2013.xlsx finds Richard Smith’s estate to be in the top 1% of New England probates recorded before 1692. Opdyck, p. 82.

[ix] Cranston, G. Timothy, with Neil Dunay, We Were Here Too: Selected Stories of Black History in North Kingstown, p. 90.

[x] Opdyck, p. 106. Bartlett, John Russell, Census of the Inhabitants of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations 1774, p. 83.

[xi] U.S. Census Bureau, 1800 United States Federal Census, https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/7590/images/4440856_00196?treeid=&personid=&rc=&usePUB=true&_phsrc=STV11&_phstart=successSource&pId=469838&lang=en-US