Black militia served along white enlistees, often multiple times.

It has been my privilege for the past seven years, since the publication of “From Slaves to Soldiers”, to give presentations about the 1st Rhode Island or “Black Regiment” in many Rhode Island communities. As I wrote the book, I came to realize that a much larger story presented itself, one that was perhaps less historically significant than the attempt to raise a “black regiment”, but one that was equally important in persuading white Americans that many blacks were in league with the cause of American liberty.

In fact, for the more than one hundred and twenty or so Patriots of Color who enlisted in the 1st Rhode Island Regiment, there were hundreds more who served in local and state militia, as well as in Continental battalions raised for campaigns in places far removed from Rhode Island.

Some of these were enslaved men served “in their master’s stead”, or on account for another family member, or even a friend of the family. Others were paid bounties to serve in their place or paid by towns to fill the quotas demanded by the Continental Congress.

This same practices existed throughout the colonies, and this article examines how the communities of Rhode Island responded for the need throughout the war, and how that response was remembered and memorialized.

Rhode Island has long prided itself that the actions taken by a group of patriots against the HMS Gaspee on the night of June 10, 1772 was the first volley fired for Independence from Great Britain. That the clamor in Providence County and the communities of Kent County for Independence rang alike in every town and village. One might be tempted to believe that the entirety of the state was as one in supporting the cause of the American Revolution, but that was hardly the case.

In Kings County, Rhode Island, many who were wary of such a conflict were the land holders of those large estates, whose farms contributed to the flood of goods leaving Rhode Island ports for the West Indies. These included bricks, timber, iron, and other tools and building materials, barrels of salted fish and mutton for the enslaved laborers on sugar plantations, and hay for the horses that drove the sugar mills.

It was a lucrative enterprise that brought great wealth to the region. Many of those prominent farmers known as the Narragansett Planters were owners of enslaved workers on their own plantations, and some owned ships or invested in ships that plied the triangle trade; shipping rum to the west coast of Africa in exchange for slaves sold in the West Indian ports, where the holds that once held the enslaved were bleached clean and then filled with sugar for the return to Newport.

But it was not only these wealthy landowners who benefited from these exchanges. Many smaller farms, lumbermen, fishing crews from Wickford, masons and craftsman, and suppliers of all kinds contributed to those exports in support of Great Britain’s production of sugar and its wholesale enslavement of thousands of individuals to meet the demand.

As one might expect, the tensions between England and the colonies of North America were of great concern to those who favored keeping such valuable economic ties to the mother country.

Such was the wealth in Kings County, that others loyalist leanings came purely from the fear of losing the consumer goods they had become dependent upon, the fine china dishware, tea sets, silverware, glassware, the silk for shirts, dresses, and cravats; as well as books, portfolio’s and prints, not to mention teas from China, fine port from France, and numerous other wines, spirits, and imported liquors.

One such “gentleman” who lived in the region was George Rome. The Englishman had arrived in Newport in 1761 at a providential moment. As it turned out, a once prominent Newport cordwainer named Henry Collins had seen his firm file for bankruptcy. Collins owned a fine home in Newport and a large portion of land with a mansion house in Narragansett on Boston Neck.

The land there was originally called Namcook by the indigenous Narragansett people, as part of their summering encampment. Lying on the northernmost portion of Boston Neck, a 600 acre parcel had originally been purchased by Capt. Edward Hutchinson whose family held the land through three generations. Henry Collins had purchased the farm and built a mansion house for his summer retreat, but risky ventures in privateering caused his fortunes to falter, and when George Rome arrived, he took the opportunity to buy the fine home in Newport as well as the “summer residence”.[i]

Rome subsequently went on to purchase adjacent properties that had been part of the original deed until he had acquired nearly the entire 600 acres of Hutchinson’s purchase. He improved the mansion house that Collin’s had constructed, and spent his summer’s there; entertaining guests from nearby Narragansett, but also from Newport and as far away as Boston in what he called “my little country villa”.[ii]

Such a lavish lifestyle of course relied upon a large contingent of enslaved workers. We will learn a little more about some of them later.

Having come so recently to Rhode Island, and perhaps by having so lavishly upheld a bachelor life of English gentility in Narragansett, many of those who favored separation from Great Britain in the fervor after the Gaspee incident, suspected Rome of being less than eager to support independence.

In 1772, a letter Rome penned to an associate in London, criticizing the governments of Rhode Island and Massachusetts, and in effect calling for the revoking of colonial charters and new governments that would be more sympathetic to the Crown, came into the hands of Ambassador Ben Franklin. The contents were soon published in newspapers throughout the colonies.

Brought before the General Assembly, meeting in South Kingston in October 1775, Rome was jailed in Kingston, and then Providence before fleeing the country on the British man-o-war Rose, then anchored off Newport.

Rome’s property was confiscated and the auction of valuables left from what the state had taken for supplies was overseen by Major James Cooke.[iii] The property was largely purchased by merchant and shipbuilder John Brown of Providence, who then resold the property to Supreme Court Judge Ezekial Gardner by 1780. With these, and other holdings; Gardner then became one of the largest owners of enslaved individuals in the state.[iv]

The enslaved individuals who had been on Rome’s farm were part of the property, and would eventually form the nucleus of a black community in Wickford. During the Revolutionary War, several of those who had been enslaved on the farm under Rome, Brown, and Gardner likely served in local militia, in Continental regiments, and even the Navy.

Ceasar Rome, sometimes spelled Rove, or Rose in the muster rolls, enlisted in Captain John Dexter’s company of the Rhode Island Regiment in 1778 and served into the time of the consolidation, being listed as a private in 6th company of the Rhode Island regiment. Ceasar would have seen all the major battles in which the RIR took part, including Yorktown. He was one of many who died some months after the battle, having contracted smallpox in transit to Philadelphia, and succumbing to the disease on December 9, 1781 in Wilmington, Delaware.[v]

The remembrance of Pero Roome as an “old Negro slave who was a relic of the Colonial Days” as noted by a 19th century historian George Gardiner, seems to indicate that he had served the town of Wickford in some way. He and his wife Sarah lived within the small community of black populated homes off Fowler St. near Bush Hill pond. They had a son named John who was a deaf mute, but later found employment at the Abby Updike Hotel in East Greenwich as a domestic worker. Pero and Sarah’s daughter Elizabeth would have several children with Henry Fairweather, another descendant of a long enslaved clan, but eventually marry a black culinary chef from Philadelphia named John Williams and left Rhode Island. Pero would find himself living in a squatter’s shack on a swampy piece of ground along the border of Tower Hill road owned by Robert Rodman. It became known as the “Vale of Pero”. His date of death and burial place are unrecorded, but two of his grandsons would serve in the Civil War.[vi]

Pero’s brother Cato served during the Revolutionary War as a seaman aboard the USS Queen of France.[vii]This old ship had been purchased from France in 1777 and outfitted by American Commissioners Benjamin Franklin and Silas Deane as a 28 gun frigate for the Continental Navy. She was to have a short, but illustrious life of service. She first departed Boston on March 13, 1779 under command of Capt. Joseph Olney, as part of a squadron under Capt. James Burroughs Hopkins who sailed the length of the Atlantic Coast down to Charleston and back, in search of the small, armed vessels the British were using out of New York to disrupt American shipping.

In less than a month the Queen of France had captured a 10 gun British privateer, whose chase led to the further capture by the American Squadron of nine more vessels. The American frigate personally escorted the captured privateer Herminia, the ship Maria, and three brigs that had been under British flag. Into Boston Harbor on April 20, 1779.[viii]

By June 18th, she was ready to sail again, now placed under Capt. John Rathbun and in company with two other Continental vessels, the USS Providence, and the sloop Ranger. These vessels sailed to the Grand Banks off Newfoundland where some 150 ships of the British Jamaica Fleet were anchored in a dense fog. The Continental Ships stole away with eleven prizes before daylight broke the fog, and while they abandoned three during the chase, the remaining eight captured vessels whose contents were sold in Boston after their return in late August, brought the Continental Congress more than a million dollars in sorely needed revenue.

In November, the Queen of France departed Boston on her final journey. Again, in company with the USS Providence and sloop Ranger, and with another frigate, the USS Boston the group set sail to cruise the waters east of Bermuda. They captured the British privateer Dolphin on December 5th, and brought her into Charleston, South Carolina on December 23rd. There the frigate remained, captive to the British assault on the city, and on May 11, 1780, the Queen of France was sunk to avoid her falling into British hands as the Americans fled the city.

For those who might wonder how an enslaved man came to be part of the crew of a Continental frigate, it would be worthy to note that Cato and other enslaved workers of the former Rome estate were at that time overseen by John Brown, merchant and shipbuilder in Providence.

It could be argued that John Brown was the most influential advocate and ship builder for the fledgling Continental Navy. It’s first ships, the sloops Katy and Washington were built by Brown and commissioned by the General Assembly to patrol in defense of Narragansett Bay. He was also the man the General Assembly charged with obtaining revenue for the war effort in Rhode Island, especially from privateering prizes and confiscated estates abandoned or taken from tory loyalists.

In late November 1775 the Katy was ordered to Philadelphia where she arrived on December 3rd was renamed the USS Providence. While there is no indication that Cato Room served on any vessel aside from the Queen of France, it’s likely that he was given that opportunity by Brown, who was actively helping to fill the crews needed for the Navy.

After the war, Cato returned to reside in North Kingstown, and had become a respected elder of Allentown by the time of his tragic death; murdered at the hands of a mentally ill black man of the same community where Cato had lived and worked for many years.

Of other known enslaved men of George Rome, little more is known. In some cases it may be that the change in ownership meant a change in name as well, as a sign of property[ix]; so that among those Browns and Gardner’s who served could be men that had originally been owned by George Rome, and part of the property confiscated in 1775.

The events at Lexington and Concord in April 1775 gave greater urgency to those in King’s County. Thomas Cranston, the descendent of Governor Samuel Cranston wrote to Beriah Brown, the high sheriff of the county on April 26, 1775:

“We are in the utmost confusion and which part we shall take is at present uncertain. I see nothing but destruction coming upon us, look which way I will..there is no person here that knows how to act or which part to take-if we should take up with the part that the government hath adopted we shall be laid in ashes-and if we take up the King’s side we shall have all the sons of liberty upon our backs”.[x]

That same year, when the call came out for able-bodied men to join both rejuvenated and new militia units, some owners of enslaved individuals took the opportunity to enlist one or more of their enslaved to serve in their stead, or in place of a family member. These men in these militia, depending upon their physical capabilities, would ultimately serve their term of enlistment within the local militia and State militia who were essential in the patrolling and defense of the Rhode Island shoreline and rivers.

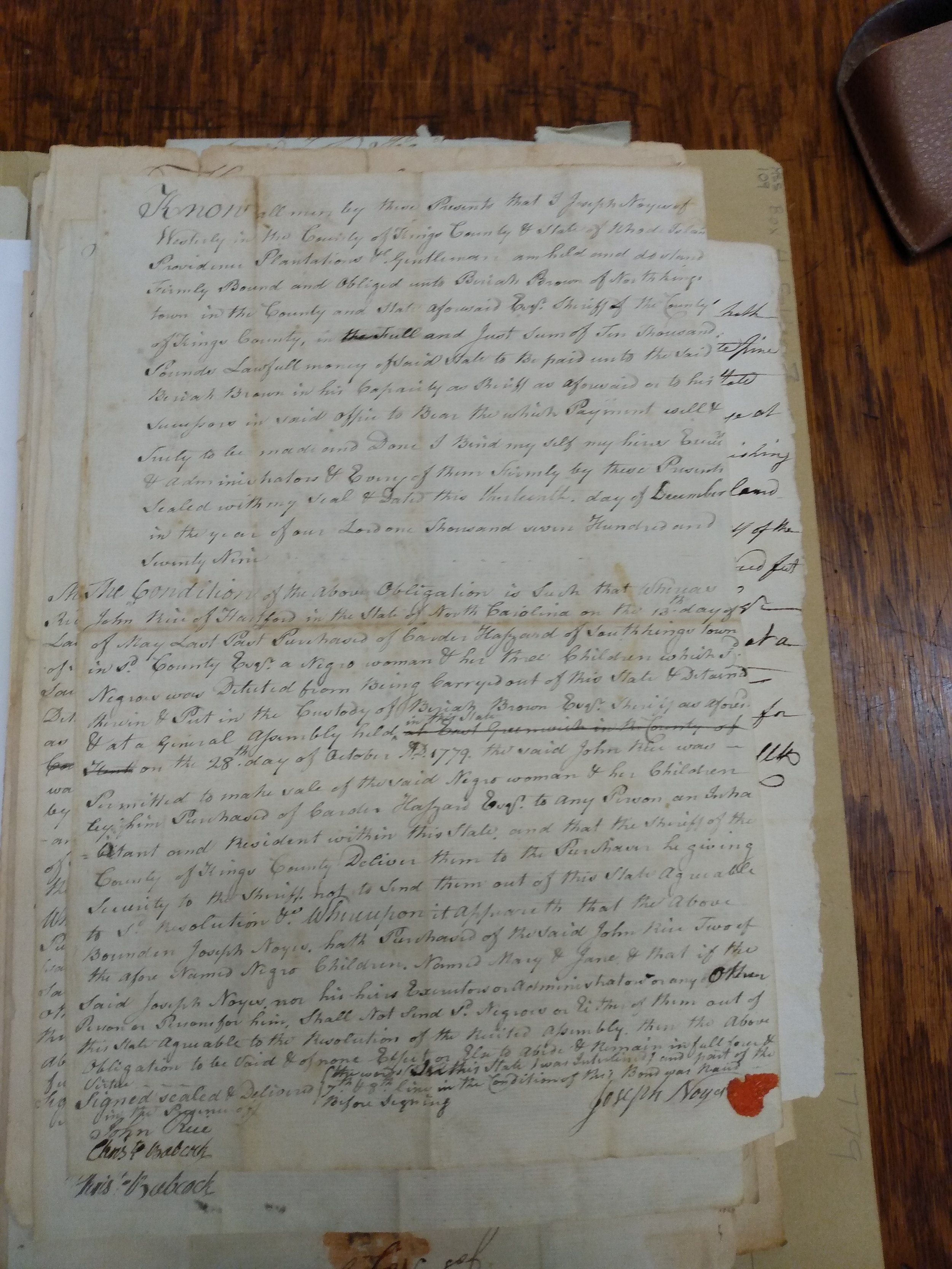

Beriah Brown kept his enslaved men close to his own interests. While Brown received missives from the Governor, and performed tedious tasks in his role as High Sheriff, he was also among the most powerful men in the state. Apart from his duties as Sheriff, his own business investments had made him wealthy. In 1748 he had invested in the sloop Elizabeth, engaged for two years in the Caribbean trade, and by the time of the American Revolution, had outfitted the privateer The General Mifflin to plunder the British fleet[xi].

As High Sheriff, no land transactions in agrarian Kings County , no probate inventory, or the sale of goods from that inventory were sealed without passing his desk[xii], including those of enslaved individuals.

On March 7, 1774 Thomas Lawton (a negro man) Laborer and Marcy ( a mustee) his wife both of North Kingstown filed a complaint against one John Franklin of South Kingstown, who on

“the first day of November A.D. 1773 with force and Arms did take and carry away one Soloman Cezar a mulatto boy of the Age of Sixteen years & son to the PCt. Marcy and the said Isaac deceased, and still unjustly detains the said Soloman…”[xiii]

The family claimed one hundred pounds in damages. A week later on March 14th, an agreement was signed that the said Soloman Cezar

“…by and with the consent of his aforementioned Father-in-law, and Mother hath doth by these present put and placed himself an apprentice or Servant to the said Beriah Brown and Amy his wife with them to serve and dwell in All Lawful Imployment in Manner of a servant until he arrives at the age of twenty one years old…”[xiv]

Conditions of his continued apprenticeship included

“…not to be unlawfully absent from his said Master nor mischief by day or Night..Alehouses nr Taverns he shall not haunt, nor play at any unlawful games….Matrimony he shall not contract nor fornication committed within said time but the Lawful commands of his said Master and Mistress he shall gladly and Every where obey…”

In consideration of Soloman’s servitude Beriah Brown agreed to

“find him sufficient meat, drink, washing Lodging & apparel during said term…to Bring him up at farming business, and to learn & instruct his said apprentice to read well in the Bible, if he be capable of learning, & learn him to write and at the Expiration of his term, to give his said apprentice one good new suit of homespun cloth”.[xv]

It’s uncertain as to the circumstances, but the young Soloman Cezar (Ceasor) enlisted in 1777, well before his twenty-first birthday, as a private in Col. James Webb’s Company of Col. Henry Sherburne’s Additional Continental Regiment through 1780.[xvi] Crucially, that means he served in the Battle of Rhode Island in August 1778.

He re-enlisted in May 1, 1780 as a Waggoner and was assigned to Col. Henry Jackson’s regiment of Stark’s Brigade on August 9, 1780 with which he served through September 20th. That month Soloman Ceasor and others of Stark’s Brigade were Court-martialed, being accused in their zeal to collect provisions of plundering inhabitants, taking “public horses from the pastures and riding them without liberty”, as well as attempting to rescue a prisoner who had been placed under guard.

Soloman Ceasor was found not guilty and discharged in November 1780. Recruited once again, he re-enlisted in January 1781 for three more years of service as a private in the 8th company (colored) of the Rhode Island Regiment. He was honorably discharged December 25, 1783.[xvii]

Brown may have given his consent to Soloman’s enlistment, though he seems to have resisted letting go of any of his domestic laborers, finally giving his slave John W. Brown for service in the local militia in 1777.

The following February his enslaved man Thomas enlisted in the Continental Army when the General Assembly had passed the Act to form the 1st Rhode Island Regiment from as many enslaved men as recruits could enlist. When Brown’s younger enslaved boy absconded less than a month later and enlisted, Brown wrote urgently to the recruitment officer on March 17, 1778

“I have heard that my negro boy Scipio has inlisted. He is but fourteen years old. I am as willing to defend my country as any man in it. But my Tom has inlisted and I have now no other boy to do anything for me. I should be very much obliged to you if you would send Scipio home again and not receive him as I have no other boy”. [xviii]

John W. Brown served in Capt. Dyer’s Militia company patrolling Boston Neck in 1777 and 1778. [xix] Both of Brown’s younger enslaved men remained enlisted. Thomas served as a drummer in Capt. Elijah Lewis’ company throughout the war.

Young Scipio also served as a drummer in Capt. Ebenezer Flagg’s company, Capt. John Haden’s company, and with Capt. John S. Dexter’s company in the Rhode Island Regiment. By the age of eighteen he was at Yorktown. [xx]

Brown’s son Christopher Brown of North Kingstown had his enslaved man Joseph enlisted as a substitute for him shortly before his death in March 1778.

Joseph Brown would serve in the local militia, and then enlist in the 8th company of the Rhode Island regiment in January 1781. He died a year later in the Army hospital in Philadelphia, January 20, 1782.

That year of 1778 was a pivotal year for Beriah Brown’s and many families in King’s County.

Records of the same February Assembly session of 1778 that passed the Act to form the “Black Regiment”, revealed that at least some of the local population were loyalists and had chosen to abandon their farms and businesses. The Assembly noted that they had received notice that

Samuel Boone, William Boone, John Wightman, son of Valentine, Ephraim Smith, Ebenezer Slocum, Charles Slocum, and Thomas Cutter, have gone to the Island of Rhode Island, and have joined the Enemy…

Sheriff Beriah Brown was then ordered to confiscate and make a full accounting of all property. In all likelihood, their enslaved people went with them. There is no indication that any enslaved of these families served in any capacity during the war.

King’s County held the largest percentage of enslaved persons in Rhode Island, and in fact, would contribute the greatest number of enlistees into the 1st Rhode Island regiment. In other cases, individuals served short “stints” in the Continental Army for the benefit of the town or village in which they were enslaved. The use of enslaved workers as a substitute in military service was prevalent throughout the war, and in every town and village in the state.

Losher Hopkins was enlisted by Admiral Esek Hopkins of Providence in the stead of a member of the Society of Friends or Quakers named John Cumstock, “who refuses to bear arms”. Losher would later serve with the 1st Rhode Island regiment, but like others, his name does not appear on the monument in Portsmouth.

Admiral Hopkins had enlisted other enslaved men he owned for the Revolutionary cause including a man named Dragon Wanton he had purchased aboard the Andrea Doria in 1776. On November 8th of that year, he penned a letter to William Ellery of Newport, asking for his assistance:

“…take some charge of him” Hopkin’s wrote, “and either send him to me, or see that he is enlisted in the service with Capt. Biddle or in any other way as you may see fit”. [xxi]

In Hopkinton, Rhode Island, Hezekiah Babcock’s slave Ceasar Babcock enlisted in the local militia in his master’s stead in 1775. He did the same in 1778 when the call came for more recruits. According to his pension application, “In the summer of that year was on the Island of Rhode Island where in an action with the enemy he saw a drummer by the name of Card killed by a shot in the breast while very near him[xxii]”

Babcock’s application testified that he had seen nearly a year and a half of service, well past the six-month requirement to apply for a pension. As there was little documentation however, his pension request was rejected. In response, two fellow soldiers from the regiment wrote to testify that they had served with Caesar. The minister of the Baptist church in Newport wrote to vouch for the two men who had written in support,

“…Being aware that the statements of “negroes” we sometimes regard with a degree of suspicion…”, and Martha Babcock wrote to the committee that

“Ceasar was a slave to my said husband before the Revolutionary War and Ceaser served as a soldier in the militia for my said husband and went to the Island of Rhode Island with the army commanded by General Sullivan to act against the British[xxiii]”.

Despite these testimonies, the Pension Board rejected Ceasar’s application, and he did not receive recognition for his service until his name was placed on the Monument in Portsmouth.

William Wanton, the enslaved man of Newport’s William Wanton enlisted in the RI militia in his master’s stead in 1777. Nearly two years later, he enlisted on March 16, 1779 as a private in Capt. Christopher Dyer’s Co. of Col. John Topham’s RI state regiment, and then again in 1780 when the State Regiment was consolidated, and became Topham’s Regiment and Battalion .

Unlike those men who enlisted in the 1st Rhode Island Regiment, service in local militia, the Continental Army, or Navy in another’s stead or for the town did not necessarily mean that you would earn your freedom. While it appears to have often been promised, in many cases freedom was not granted to these men, at other times, it appears that strings were attached to promises once made.

A revealing letter written November 3, 1777 by Oliver Whipple of Portsmouth to Major Samuel White on behalf of Primus Nelson, the enslaved man of Jonathan Nelson.

“Mr. Nelson told him” writes Whipple, “that if said Primus cou’d get enough to pay him, he should be free; but avarice has got so strong Possession of Mr. Nelson that I fear he will violate his word with the said Primus & turn his promised freedom into dispairing Slavery”.[xxiv]

As the war progressed, and the demand for troops grew greater, these communities struggled to recruit new enlistees and soon found the way to meet the quotas was to offer bounties for enlistment. These came from both the town, and in other cases from individuals who paid a bounty to have another man serve in their stead.

Examining the enlistees from the July 1780 Six Month (Levies) Continental Battalion we find that many of those paid such bounties were black veteran who had enlisted earlier, served their term, and re-enlisted for the Six Months. A majority of these men would go on to serve longer terms, even unto the end of the war.

Here are a few examples:

Private Josiah Simons, “black and born in Richmond”, Rhode Island enlisted initially in June of 1778 serving in Capt. Christopher Dyer’s Co. of Col. John Topham’s R.I. State Regiment. He was discharged in 1779, but re-enlisted to serve “for the town” in the six-month levies, July-November 1780.

Private Charles Daniels, an indigenous man born in Charlestown, enlisted initially on June 9, 1778 in Capt. Christopher Dyer’s “colored” company as well and was discharged in 1779. The following year, he too enlisted for the six months in the Continental Battalion for the town of Jamestown. [xxv]

Providence merchant Nicholas Power received a bounty for “his Negro Ceaser” for six months service on June 15, 1780.

On June 21st, Pomp Reaves was ”among those who took the oath of allegiance and were mustered into the Continental Service”.

Private Prince Arnold of Smithfield also enlisted in Capt. Christopher Dyer’s company, and with others was discharged in 1779. He too served for the town where he was born for the six months (levies), but continued his service after November 1780. By March 1781, he is listed on the muster roll as a private in Capt. Daniel Mowry’s company of Col. George Peck’s R.I. Militia Regiment.

Father and son, James Anthony aged 39, and Elisha Anthony, a 17 year old “molatto”, both from South Kingstown, also served six months with the Continental Battalion for the town of Johnston in 1780.[xxvi]

Primus Atkins was born in Africa, and enslaved in Johnston. By the time of his enlistment for the town in 1781 he was forty years old. Atkins served in Capt. Joseph Allen’s company for the six month levies, and thereafter in a regiment of the Rhode Island Militia for the remainder of the war. Jeremiah Ceaser, an enslaved man owned by John Waterman also enlisted in Johnston that year.

A bounty was paid to veteran Bristol Olney in February 1781 who enlisted on behalf of the town of Cumberland. The town sent the enslaved man’s pay to his owner Capt. Amos Whipple.[xxvii]

The town of Barrington, Rhode Island also paid bounties to owners of enslaved men who were enlisted into local militia or to fill the town quota throughout the war. On June 20, 1777 the town approved payment of L44 to brothers Thomas and Matthew Allin, Joseph Reynolds and Matthew Watson, stipulating that the negro Pomp Watson had enlisted on his account. On December 2, 1780, Hannah Smith of Barrington, Rhode Island was paid L15 ”as a bounty for her Negro man Pomp”[xxviii].

Thomas Reynolds was enlisted in Capt. Thomas Reynolds company in 1777, and by May 1778 part of those that formed the “Black Regiment”. He continued to serve being listed in 1781 as a private in the 6th company of the Rhode Island Regiment. He was transferred from the Regiment to the Corps of Invalids on May 1, 1781. [xxix]

Pomp Watson served as a private in Capt. Thomas Cole’s Company of the 1st R.I. Regiment. After a winter at Valley Forge, he was by May 1778 listed as a private in Capt. Thomas Arnold’s detachment, which would be trained under Von Steuben, and merge with later recruits to form the Black Regiment. He served in the Battle of Rhode Island, and in patrolling Barber’s Heights in the months after. He was Honorably discharged on May 20, 1780. [xxx]

Pomp Smith served six months Continental Batallion duty for the town of Barrington from July to December 1780. He was 36 years old.

As for the enslaved men of the Allin family, theirs is a fascinating story:

Tucked away from the center of town lies an old cemetery with a cluster of well-maintained monuments at one end, and on the other; a lone, early 19th century gravestone for Scipio Freeman, a long recognized veteran of the revolution in the popular remembrance of the community.

Though he was known as an enslaved man belonging to the Allin family, and listed on the roll of able bodied men above 16 to serve in the town militia, there is no evidence to support that he served in the 1st Rhode Island Regiment, or even in the town militia. Brig. General Thomas Allin and brother Captain Matthew Allin were both officers of the local militia but do not list him upon muster rolls kept during the revolution. Even the native born historian Thomas Bicknell who wrote the town’s history could only admit that

”While it is well known that this faithful slave was in the service of the town and state during the war, I have not been able to locate the Co. or Reg. ; died April 30, 1816 aged seventy years”.

As a direct descendant of Amy Bicknell, wife of Thomas Allin who owned Scipio, the historian likely heard the family lore first hand, but by then it had become a story that had evolved from a singular incident to Freeman being a soldier in the Continental Army.

Bicknell had a passion for monuments. Among those he left in Rhode Island were a tombstone to Canonicus, the Narragansett sachem near his seat on Devil’s Foot ledge. Another Barrington monument is to those “good and faithful slaves of the community”.

The historian in fact, begins his chapter in the town history on “Domestic Slavery and Slaves” with the astonishing claim that

“The Institution of slavery has never flourished in Rhode Island…The spirit of independence, of freedom of thought and of religious toleration was, in its nature, hostile to human bondage”.

Later in the same chapter he documents family ownership and sales of enslaved men, women, and children in the town, and lists sixty-eight known enslaved individuals that were domestic workers or laborers for Barrington families during the latter years of the 18th century, including Scipio Freeman. [xxxi]

So what of Scipio Freeman ? Was he among the ”six slaves and several men over sixty who entered the service” along with the eighty-three “effective men for service” that mustered for the march to Boston in 1775? Or is he remembered for an event that likely included some of the enslaved he shares the space allotted them in the Allin Yard.

Somewhere among the fieldstones that lay buried around Scipio Freeman’s gravestone is the resting places of Prince Allin, who served in Capt. Thomas Allin’s Company of Col. Crary’s Regiment as the property of the Allin family.

Two other enslaved men of the family were later given bounties to enlist on May 17, 1777.

Jack Allin was given a bounty of eighteen pounds from Levi Barnes and John Short Jr.

Richard Allin received a bounty of fifteen pounds from Mathew Allin and George Salisbury.[xxxii]

While these men were given monies for serving as a substitute, Thomas and Mathew Allin received forty-four pounds each in compensation “for their negroes” from the Town Council in June 1777. [xxxiii]

All of these men show on the muster rolls under the spelling “Allen”. Prince is listed as serving as a private in Crary’s R.I state Regiment in 1776, and from May through October of 1778. Both Jack and Richard Allin would serve in Col. Thomas Cole’s Company. Jack was a private in Capt. Thomas Arnold’ detachment of the early “black regiment”, but died on May 18, 1778 before the Battle of Rhode Island would test the recruits mettle. Richard served in Capt, John S. Dexter’s company from 1778 until being honorably discharged on May 22, 1780.[xxxiv]

So what of Scipio Freeman and his role with the family in the Revolutionary War? What follows is my hypothesis of how this enslaved man’s actions may have earned him the reverence of the family he served, and their community.

The Allins were descendants of William and Elizabeth Allin who had married and settled on Prudence Island sometime before 1670. The family homestead and lands were still intact on the island in the years before the Revolutionary War. Though the Barrington Allins were three generations removed from the island, the family still remained connected, and it is likely that brothers Mathew and Thomas still held a vested interest in the agrarian opportunities the rich grazing grounds, fertile land, and protection for valued livestock the island long offered.

In the wake of the Gaspee affair in Warwick, Rhode Island in 1772, British patrol boats had plied Narragansett Bay, occasionally holding coastal towns hostage under threat of cannon fire while residents scrambled to raise provisions to save the town from destruction.

Within two years, the British Naval Commander James Wallace had become the nemesis of Rhode Island merchant vessels. By the summer of 1774, Wallace patrolled the Rhode Island coastline in the HMS Rose, and with sister ships the HMS Glascow, and HMS Swan; routinely raided and plundered coastal communities and islands offshore.

One such island that had caught Wallace’s attention was the six-mile long Prudence Island.

Lying an equal mile and a half distance from Warwick Neck to the west and Bristol to the east, the island was long used by farmers to keep their livestock safe from predators. By 1774, thirty-three families also called the island home.

On August 24, 1775 Wallace landed two hundred men on the island and plundered the farm of John Allin, stealing twenty sheep, thirty turkeys, and bushels of corn as well as hay. The following November, another raiding party stole clothing and furniture-even a large mahogany desk-from several homes, as well as two horses and geese[xxxv].

When the impudent Captain wrote to Governor John Wanton, demanding more goods from the island, Militia Captain Samuel Pearce heard of the 2nd Portsmouth Company decided the time had come to make a stand. He ordered all women and children off the island, and all that remained were thirty-two men under his command, among them eleven enslaved African-Americans[xxxvi], most likely the property of the extensive Allin family.

These were taken into the company, given weapons, and taught to use them for the coming battle. With their forces soon bolstered by men of the Kentish Guard from Warwick, and militia from Bristol and Tiverton, they faced off, and fought the invaders on the 13th of January; driving the British back to their vessels before retreating from the island that night.

Was Scipio Freeman and the other enslaved men of the Barrington Allins among the eleven patriots of color who fought that day?

The 1774 census shows that John Allen (as the name is spelled in the census) had no enslaved men in his household in Portsmouth and thus, not on his property on Prudence Island. No other Allens on the island but Ebenezer Allen held an enslaved person among them, and he had but one in a household of twelve.

By contrast, Thomas and Mathew Allin held five enslaved persons apiece in considerably smaller households in Barrington. The census does not list blacks by male or female as it does for whites, or even categorize them under an age group as it does for white families, so we have no way of knowing what males beyond Scipio, Prince, Jack, and Richard may have been owned by the two brothers. Could it be then, that the enslaved of these militia commanders were sent to the farm on Prudence Island in preparation for the Island’s defense, and unknowingly became, the first enslaved men that were given arms for the first time in defense of the Colonies?

If so, then Scipio Freeman, Prince, Jack, and Richard Allin are greater heroes than we understood them to be. It may also explain why, along with consideration of the other men’s later service, they were all accordingly buried, even at a distance, in the family plot.

If Scipio Freeman never fought another day, the family would have still held the story of his fighting for their land in high esteem. Not only as a great tale from the Revolution, but likely also as an example of the family being among those benevolent owners of the enslaved, so much so that their enslaved rewarded them with loyalty and protected their property.

These men in fact, stood their ground with the others and were among those that drove the British back to their ships after an all-day skirmish that left a dozen British regulars dead and the Americans no worse for wear.

It also stands to reason that if these enslaved men of the Allin family defended the property and the island with others that day, it may be why bounties were offered by men of the town, and the origin of the legend of Scipio Freeman’s service in the American Revolution.

But again, this is mostly how the 19th century historian would want us to see the story, a version propagated for so long that it became part of the community’s remembered history. It’s tempting to believe that Scipio and others willingly defended their master’s family property that day, but that may not be true.

Thomas Allin was a man well regarded for his capacity to “break-in “ new enslaved men, or even those who were troublesome to their owners. A receipt from Nathanial Smith of Barrington written on January 26, 1790 records payment to Allin for punishing his enslaved man Caeser as “Allin thought fit”.

Bicknell writes of the lives of some of those in Barrington who served and returned.

Pomp Watson continued to live in Barrington after the war. According to local history, he married a woman called Doctoress Phyllis who religiously walked from Barrington to her home church in Swansea for the “feet-washing” ceremony, that was a popular reenactment in particular of early Baptist churches, of Christ washing the feet of the poor.

Prince Allin married a woman named Henrietta “Writty” Brown. They had a son named Pero, who became a noted fiddler. He married a woman from the coast of Guinea, and they were attending members of the Congregational Church. The couple had seven children, Hannah, Clark, Rhenkin, Stephen, Olinda, Mary, and Lurane and lived on what was later named “Jenny’s Lane”.

Richard Allin and his wife Margaretta had eight children, Lydia, Richard, Ceaser, Theodore, Olive, Jemima, Sarah, and Charles. Town historian Thomas Bicknell would write that his family and their descendants were among the last people of color “to pass away from our midst, within the memory of those now living. They long outlived the period of slavery”. [xxxvii]

Despite the appearance of acceptance within Barrington and other Rhode Island communities after the Revolutionary War, these veterans often remained marginalized, having to return to work for their old masters and others as well to earn a living. As white-washed as these histories often are in their acknowledgement of black heroes, their true stories are now being uncovered in pension files and in records and written recollections that are still coming to light today.

[i] Cranston, G.T. The Whole History of Rome Point The View From Swamptown, The Independent, December 2, 2018 http://independentri.com

[ii] Ibid.

[iii] Bartlet, ed. Records of Providence Plantations and the State of Rhode Island Vol 3.

[iv] Independent, December 2, 2018

[v] Popek, Daniel M. They Fought Bravely…But Were Unfortunate: The True Story of the 1st Rhode Island Regiment 541

[vi] Cranston, G.T. The View From Swamptown: From Slaves to Soldiers, the Roome family left a legacy The Independent February 17, 2019

[vii] Grundset, Eric G. ed. Forgotten Patriots: African American and American Indian Patriots in the Revolutionary War (Washington D.C., National Society of the Daughters of the American Revolution 2008) see Miscellaneous Naval Service Records, p. 655 See also Claims Barred by the Statutes of Limitation, 11thCongress, 3rd Session, No. 216 American State Papers, Vol. 9 (Washington D.C.: Gales and Seaton 1834), 397

[viii] Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships, see Frigates: USS Queen of France. The American ship was named for Queen Antionette

[ix] An example of this are the deeds of sale concerning two enslaved workers owned by Thomas G. Hazard to Rebecka Martin reading in part “a certain Negro boy named Newport Martin now the property of Rebecka Martin…and the same for “a certain Negro woman named Bettey”. RIHS Mss 1026, Folder 14, Legal documents.

[x] Beriah Brown Papers, Box 4, Folder 7 Rhode Island Historical Society

[xi] Stattler, Rick Finding Aid Beriah Brown Papers

[xii] A desk that has resided for years in the small summer “law office” of Daniel Updike. Brown may not have known that he was related to the Updike’s through the marriage of Kathryn Updike Goddard whose family donated the desk to the historic house museum.

[xiii] Beriah Brown papers Box 3 Folder 6 1774

[xiv] Ibid.

[xv] Ibid.

[xvi] Popek, p. 450, 667-668

[xvii] Ibid.

[xviii] Beriah Brown Papers, Box 4 Folder 7 Rhode Island Historical Society

[xix] Popek, p. 665

[xx] Ibid, p. 423

[xxi] RIHS Mss 491, Box 2 Folder 2, Hopkins Papers Vol 1. (letterbook) 1776-1777

[xxii] Pension Application 339, National Archives.

[xxiii] Jack Darrell Crowder African Americans and American Indians in the Revolutionary War McFarland & Co. 2019 pp. 16-17

[xxiv] RIHS Mss 9001, Box 9

[xxv] Popek, 325

[xxvi] Grundset, 204

[xxvii] RIHS Mss 673 sg 2, Series 4, Subseries E, Box 3, Folder 101: Subscriptions for Bounty

[xxviii] Bicknell p. 365

[xxix] Popek, 702

[xxx] Ibid., 716

[xxxi] Bicknell, Thomas History of the Town of Barrington, Rhode Island 409

[xxxii] Ibid., 362

[xxxiii] Ibid., 365

[xxxiv] Popek, 658=659

[xxxv] Geake, Robert A. New England’s Citizen Soldiers: Minutemen and Mariners The History Press 2019 p. 39

[xxxvi] Grandchamp, Robert From Fence to Fence: The Battles of Prudence Island Journal of the American Revolution Oct. 18, 2017

[xxxvii] Bicknell, 405