With the outbreak of the American Revolution, long marginalized Indigenous and black Americans residing within the state of Rhode Island found that their skills and labor, even their abilities as soldiers and waggoneers suddenly made them of greater value than they had ever been before. But then, the state was made up of communities that had grown dependent upon enslaved and menial laborers who in some towns and villages outnumbered the able-bodied men fit for service.

Rhode Island’s passing of the Act allowing patriots of color to enlist in the Continental Line opened the door politically for other states to do the same; though both indigenous and black enlistees in militia had occurred from the war’s beginnings, especially in New England. Many historians today, see Rhode Island’s actions, and the other states public acceptance of patriots of color within their militia and Continental units as a sea change in the perception of the character, courage, and capabilities of black Americans among the citizens of the new Republic.

At the time of the American Revolution, the majority of those enslaved men who enlisted in militia or in Rhode Island’s Continental regiments were American born, often the third or fourth generation of an enslaved couple initially brought together at a single plantation. As a result, many of those returning veterans after the war had long enslaved family members waiting for them back home.

The younger generation of officers, and the soldiers who served in the American Revolution likely saw enslaved people differently than the previous generation. As for the officers, some were raised by black women who served their mistress as a nanny. For those who enlisted, being largely poor and transient through the majority of the war; working alongside people of color was a common occurrence .

But while it may have been a watershed moment in the way some white citizens viewed people of color, and certainly bolstered the efforts towards the Gradual Emancipation act that was signed in 1784; once the economic realities of independence followed those soldiers home, there was little support given for their efforts to make a livelihood and much in the way of oppression, in towns that broke up families, indenturing children while expelling parents to the town of their birth. Sometimes this was the same town for the couple. Sometimes not. Such a policy also limited opportunities for people of color who felt they had little choice to leave the town of their birth in such case their circumstances worsened.

It is a fair statement that a warm welcome did not await those returned after being warned out of another town. It meant that the family, the individual, the single mother, would have to begin again, and prove their worthiness as citizens.

Whether earning their freedom by placing their lives in jeopardy along with white soldiers in the Revolutionary cause, by being emancipated, or by self-purchase outright, freedom always needed to be earned and earned again for those living in the wake of the war of Independence.

Black labor north and south was often much the same as on farms in New England before the explosion of the cotton industry.

When Stephen Hopkins was warned out of the Society of Friends or Quakers in 1772 for reluctance to free his last enslaved woman Phebe[i], he believed that while enslavement was against God’s nature, it would be irresponsible for him to free someone with little prospect but poverty before them. While Hopkin’s case is singular in that his 1760 will included instructions for the care and education of the enslaved he bequeathed to his wife Anne, his son and daughter; other owners of enslaved individuals long touted an anti-abolitionist stance that it would be inhuman to free enslaved people who had no skills, could not read deeds or documents, and would surely be unable to generate a living for themselves.

More recently, misinformed politicians are attempting to stylize the era of slavery in a more positive light, promoting the idea that those blacks enslaved acquired skills that they could then parley into meaningful work after emancipation.

While a small percentage of enslaved people learned new skills during their period of forced labor, plantation owners often relied upon skills already known by African people, and often sought enslaved workers with those skills. Aside from knowledge about agriculture and medicinal plants, African people hold a long history of pre-colonial skills in iron work, silver and goldsmithing, as leather workers, and weaving[ii].

Those individuals who were “clever” in their master’s eyes might be taught new skills, but they were taught for the plantation or the master’s business’ benefit, though some enslaved certainly learned that to compose themselves in a certain way before their master might benefit them in the way of learning these skilled tasks and if such skills were practiced in the house, such usefulness might lead to better living conditions. Another generation would pass before those who were enslaved before the Act of 1784 were either manumitted or disappear from the census rolls.[iii]

Such skills also led to wages for some blacks by the time of the Revolutionary War. As early as 1776, we find that Katherine Greene paid wages to Sarah Sambo, Betty Quaco, Mercy Ceaser, Vilot, Black Hannah, Barbary Cuff, Betty Newport, and others for breaking, hackeling, and spinning flax, a popular cloth used to make summer shirts, jackets, as well as coarser shirts and headwear for the laborers.[i]

The following year of 1777, Moses Brown settled the accounts of his candle works, paying his former enslaved man Tom the wages owed for three years since his emancipation, amounting to “the whole of 70 dollars”, along with separate wages to men named Yarrow and Newport. [ii]

While free blacks and indigenous men were regularly hired as laborers, they always fell under suspicion if a rash of petty crimes were committed, no matter that there were a larger number of white veterans, displaced or transient also looking for temporary labor, room and board.

Part of this underlying tension arose as the black population in the state shifted dramatically in the years during and after the war. While the 1774 census shows over 900 enslaved people in South County, by 1790, the number of enslaved were down to 297 individuals out of a population of over 1,700 blacks. By 1800, the number of enslaved blacks in the County is listed as 124 individuals out of a population of 1,023[iii]. Many had removed to Providence, the city seeing a jump in population from 475 individuals in 1790 to 656 a decade later. [iv]

Still, there were those, especially in South County who held onto slaves long after emancipation. In 1800 there were still 168 enslaved workers recorded in Rhode Island.[v]

As late as 1803, Elisha Potter Jr. purchased two black children from Asa Potter Sr., both children born to an enslaved woman twelve and fourteen years respectively, after the Emancipation Act of 1784.[vi]

Those blacks throughout the state who had earned their freedom or been emancipated after the war often lived on the margins of existence, co-existing with blacks and indigenous people still enslaved, sometimes their own wives and children. they labored at multiple jobs to keep themselves and their families intact. If they were unable to earn a living, they often faced being separated, or “warned out” to the communities of their birth; a practice many communities adapted to avoid these individuals becoming “a burden to the town”.

In 1783, the town of North Kingstown passed a law against “the taking in of strangers”, and in particularly, the “harboring of blacks”. The town constable decreed

“…Every black person who abides in this town not being inhabitants of this town to depart said town and direct the people who harbor them to (transport) them out of this town”.[vii]

In 1787, resident Giles Pearce was called before the town council for “his taking a black family (into) his house…”

Over a period of twenty years, until 1813, the town removed or indentured at least twenty-one individuals of color.

Providence also routinely called upon people of color they believed to be transient or “chargeable” to the town, especially women of color. In July 1782, the council ordered an entire household of women of color to appear before the council for examination. The council charged Patience Ingraham with “Keeping a common, ill governed, and disorderly House, and permitting to reside there, persons of Evil Name and Fame, and of dishonest conversation, drinking, tipling, Whoring and Misbehaving themselves to the Damage and Nusance of the town and great Disturbance of the Public Peace”. [viii] Women of color who by choice or desperation used prostitution as a means to survive were held in disdain by town officials. These women were often manumitted of necessity as the economy left large and small estates struggling to maintain household staff. As women aged they often had fewer choices and became transient, shuffled from town to town by authorities.

In January 1804, the town council, not above enacting a puritan code of law, ordered Bess Bowers, “a transient black woman”, to “leave town or be publicly whipped”. [ix] Between 1795 and 1830, the town expelled at least twenty-nine women and children.

Another challenge for people of color in gaining acceptance in the labor market was surely the longstanding effort by white supporters and free blacks in Newport and in Providence to emigrate from the United States. The Free African Union Society was formed in 1780 by a group of free blacks who desired to emigrate to Africa and form a colony of free blacks there. By 1789, the Newport organization addressed a letter to “all the Africans in Providence” , urging citizens to join their efforts “for the common good”.

The letter urged blacks to take heed of the growth of slavery in the Southern states and the West Indies, even as it declined in northern states, and encouraged those blacks in Providence to come together with their peers in Newport “to consider what can be done for our good and the good of all Africans, and in the meantime we…are ready to do all the good we can, whether we are called to go there, or stay here”.[x]

On September 22, 1789 a group from Providence responded, and developed a subordinate group in the city that included the roles of President, Vice-President, Treasurer, Deputy Secretary, a moderator, six representatives, and a sheriff. The two groups worked together on providing relief for families in both cities, and by 1794 with aid from white contributors, even financed an expedition for the colony’s potential site in Sierra Leone.

These efforts while no doubt sincere for those people of color who shared the belief that they would never be equal to the white population in the United States, but that conviction ran counter to the majority of Rhode Islanders of African lineage who identified themselves as American.

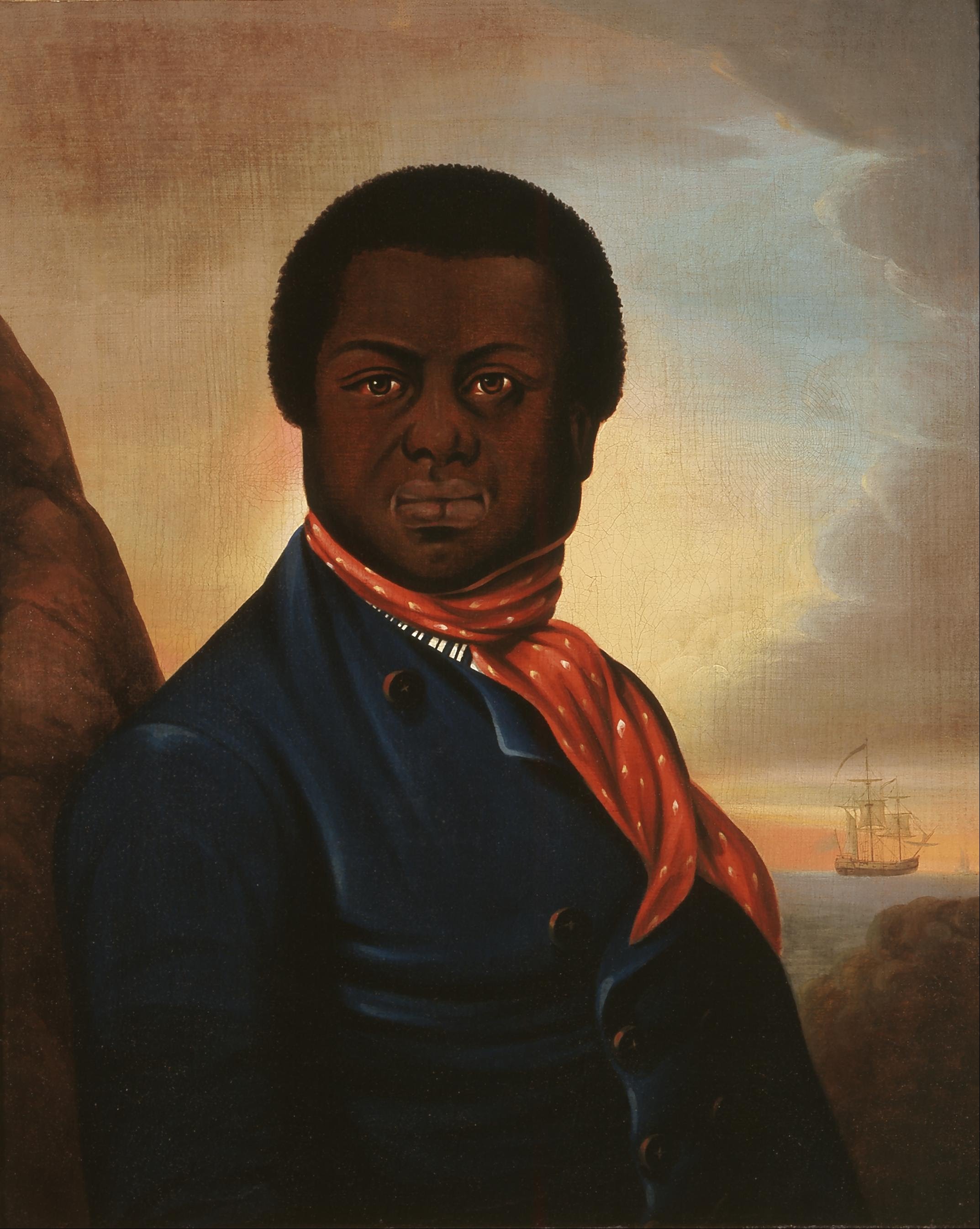

Indigenous veterans also found themselves constrained between two worlds. Some returned to their tribal lands and found that their property had been retaken by the tribal council in their absence and given to others. As it was also a time of extreme poverty for the Narragansett, many left the tribal reservation assigned by the state in 1700 but now dwindled by the sale of lands, and found work where they could, whether it be on whaling or fishing vessels from one of the regions ports, or dockside where there were always hands needed to be hired. Black laborers also long signed onboard Rhode Island vessels where, once at sea, they were among equals with the rest of the able-bodied seamen.

Image of a black mariner, courtesy of Wikipedia commons

Indigenous veterans also found themselves constrained between two worlds. Some returned to their tribal lands and found that their property had been retaken by the tribal council in their absence and given to others. As it was also a time of extreme poverty for the Narragansett, many left the tribal reservation assigned by the state in 1700 but now dwindled by the sale of lands, and found work where they could, whether it be on whaling or fishing vessels from one of the regions ports, or dockside where there were always hands needed to be hired. Black laborers also long signed onboard Rhode Island vessels where, once at sea, they were among equals with the rest of the able-bodied seamen.

People of color without the youth and needed skills for such labor naturally gravitated toward work opportunities, and often became apprentices or assistants to blacksmith’s, coopers, cordwainers, chocolate grinders, tanners, stone carvers, and other skilled craftsman in Rhode Island’s communities.

Longtime Providence blacksmith and shopkeeper Jacob Whitman had mounted a ship’s figurehead of an Ottoman warrior on his house alongside the Providence River by 1750 as a “navigational marker[i]. The 1774 census shows the household of his blacksmith son and namesake, counted 14 people, including 6 people of color and 1 indigenous servant. A family history written by his granddaughter Jane Keeley recalled that

“… he had a large forge near the cove. I think it was worked by a large number of hands. He was the owner of a number of slaves, the most trusty one was Baine, he had the care of the forge”[ii].

She listed his enslaved people as “ Primmy No Nose…Cato, Pomp, Sisser, Card, Amy, Tullis, Nancy, and Dorcas”. Primmy and a “Temp” No Nose are listed as former servants of Cyrus Butler in a 1768 survey that listed 184 black men in Providence. He may well have been a paid laborer by this time along with others in the house that worked in the blacksmith shop[iii]. Keeley recalled that the enslaved “lived in a row of houses near his own that faced Westminster Street[iv].”

The 1790 census shows that Providence still held thirty-six enslaved workers among twenty-four slave holders. The majority of these were domestic servants, fifteen of these being men of substantial means, but owning but one enslaved worker. Some prominent families like the Nightingales held eight enslaved domestics among them, while William Smith held four, Samuel Chace held three, while Ebenezer Thompson and Aaron Throop each claimed two enslaved individuals. Three women, Mary Young, Elizabeth Cozens, and Hannah Cook all claimed one domestic enslaved worker.

That same census shows that slaves were now a distinct minority of the black population in Providence, with 26.8 % living in black-headed households.[v]

With the advent of the industrial age, opportunities arose in the early years of its development for those who could work independently from their own homes.

Cotton Manufacturers Almy, Brown, & Slater paid free blacks from its inception for a variety of tasks used in the manufacturing process,, often done at home.

From 1789-1791 the firm regularly paid Providence residents and veterans Bristol Rhodes and Primus Brown, as well as Cudge Brown, Primus Hopkins, Prince Cushing, Phillis Alderedy (wife of Prince). Marge Alderedy, Providence Brown, and Phebey Shaw for spinning. [vi] In addition, early histories of the mill report a former enslaved man named Prime who was hired to turn the motive wheel for the mill.

Blacks had been hired to make the roads going to the mill, and in the construction of the mill itself. The investors also paid an unnamed black man to make gunpowder for their use. But by 1793 all work was done inside Slater Mill on machines, and while they held the skills, no free blacks were hired for the mill, or their children;[vii] though there is notation that the mill gave an order through 1794 to one “John Bucklins (, a) black man, for work at Pawtucket”.[viii]

In South Kingstown, Isaac P. Hazard established a mill and sought labor from the pool of black laborers in that town, paying wages for spinning, weaving, and carding to Ann Brown (negress), Mary Trim (negress), Sharper Boss, Betty Potter, Hetty Stanton (negress), Judith Hazard (negress), and Joseph Potter. [i]

In Hopkinton, Rhode Island, George Hopkin, a veteran of the Revolutionary War and a local militia leader, operated a general store and relied upon several former enslaved workers for weaving. From 1794 through 1811 he paid numerous laborers, among them were veteran Sezar Babcock, his son Robbin, Rose Boss, Samson Samuel, another possible veteran from Massachusetts, and a girl named Barberry. He also paid wages to an indigenous man named Lyman Kerdan. [ii]

These southern regions of the state were among those that once held the largest enslaved population. Daybooks and diaries reveal that many lived a hand to mouth existence, often working on three or four farms a week to earn a meagre living.

Smith’s Castle, or the Updike Plantation, as photographed by the author in 2017

Daybooks for the Updike plantation of North Kingstown shed light on this existence. The house retained two domestic servants named “Simcco (the son of Robe Smith) who lived as a “volunteer”, or as an apprentice, and a girl named Mannie, who “came to work here by the month” at five dollars a month. Mannie was also paid in bushels of corn, peas, bushels of rye, and in one instance, a knife[i].

Laborers for the plantation were hired for specific, limited tasks throughout the year of 1791:

Henry Northup Jr. was hired for 4 days work in January.

George Fowler was hired as a laborer, his work recorded as Breaking flax in winter, hoeing and planting peas in April, cutting stalks and gathering seaweed for fertilize in summer, and helping with harvest by picking feed corn and apples.

Nathan Onion, an indigenous man, was hired for six months at five dollars a month for picking corn and cutting wood.

James Wightman worked from November 1791 into early January of 1792 and earned wood, corn, dried codfish, and on Payment in January, 12 ½ pounds of fresh cod.

Henry Eldred was also paid in cash and corn. One man name Will Pitt-Short, was paid in a $6 pair of shoes.

In the ensuing years of 1795- 1801, recurring names of former enslaved workers recur in the ledger, including Revolutionary War veterans Stafford Scranton, Ceaser Updike, Bristol Congdon, and mariner Samuel Sambo.

In 1797, Newport Hall “came to work by the month at 8 dollars per month”. His brother Joseph also worked sporadically at the farm. Hall was also a veteran of the Revolutionary War, having served in Connecticut’s 3rdRegiment of the Continental line.

In 1800, Ceaser Northup was paid to work with Paul and Pierce Austin in building a stone wall on “the left side of the lane to the house”

Thurston Austin also worked from January through October, and included in his accounts on June 19, 1800 “lost one day for Negroe Lection”.

Pero Gardiner also worked as a farmhand in May and June. Part of his payment included the use of ½ acre for planting his own crops.

Black and Indigenous laborers working on the Updike plantation in 1801 included Samuel and Stafford Scranton, Samuel Sambo, and Daniel Onion, a well-known indigenous man and shoemaker.

Elsewhere in South County, blacksmith “Nailer Tom” Hazard would record with regularity the enslaved and former enslaved workers who labored, lived, and died in the region.[i]

On October28, 1792 Hazard records that “My wife delivered Mingo Potter two dollars that Robert R. Hazard gave me to get soum wood cut. He recorded eight years later on July 7, 1800 of an accident at John B. Dockray’s farm where “George Robonson a Negro man got badly hurt” .

Black and Indigenous laborers continued to find odd jobs to sustain themselves. This was especially difficult for women, who lent their labor to a variety of tasks from cooking, cleaning, and laundering to being seamstresses, nannies, and wetnurses.

An entry for December 27th reads “Else a Negro Woman washed for me. She (comes) t stay one week”.[ii]

On January 8, 1791, he notes that “my wife paid Else a negro woman that work’t fore me all day yesterday”. [iii]

Hazard and his wife paid at least three other women of color for washing clothes, including Robe Congdon, Jinn Jacob, and an unnamed “negroe woman” who in December 1805, “Washt here ¾ of a day the last 4 day(s) and my Wife Paid her for the saim”. [iv]

Other skills gave indigenous woman opportunities for some employment. In June of 1791, Hazard paid “Three (Squaws) that (bottomed) my cheers (chairs). And paid them all but one bushel of corn”. [v]

In July of 1824 Hazard recorded that “two Indians lodged here last Night coume to bottom chares.. They bottomed foure Chares.” The next day, “they bottomed foure more Chares, paid them on an order from Isaac P. and Rowland G. Hazard’s store.”[vi]

The journal of Daniel Stedman (1826-1859) covers a time in the regions history when many former enslaved people in the region were dying off, and their descendants as well as those still enslaved within the communities of South County continued to live a hardscrabble life. Stedman himself lived a simple life, farming in summer and making shoes during the winter. He also took day jobs and often worked beside enslaved and free blacks to earn a day’s labor.

Stedman also hired indigenous and “colored” laborers throughout his long life, and was familiar with people of color within his community, especially John Potter, a veteran of the 1st RI Regiment, Boston Port, James Hull, and John Brown.[vii]

In Warwick and East Greenwich, communities that relied upon maritime trade, black and indigenous laborers found work in ropeworks, on the docks, and providing other labor for merchants in the villages. One mercantile firm that provided work for such laborers was E&C Greene, mercantile.

Elihu and Christopher Greene were involved in the family forge at Potowomut, and also established the mercantile partnership which included the sloop Two Brothers. The firm shipped anchors from the forge, as well as staple goods, produce, milled grain, and other stocks up and down the east coast as well as selling goods locally, including shoes, spun wool, medicine and alcohol.[viii]

From 1786-1792, the firm consistently hired Samuel Sambow (Sambo) noting that he had lost a day’s work attending the “negroe election” in June 1790. He was hired again for a one day’s work in November 1810. Sambo was largely known as a mariner out of Wickford.[ix] His brother Job Sambow also worked occasionally for the firm, and in 1811 struck a deal to “rent” a lot in payment of “a stone wall built on the property”.[x]

The brothers hired other blacks for unspecified labor, including “Mr. Howard & Lady”( who “lost” a total of eight days, attending the black election, Chris Sambo(w), Ceaser Brown, Cato Sweet, Fortune Dyer, George Gardner, and a “black boy” named William Thomas between 1811 and 1827.

Farm labor throughout the agrarian age was labor intensive

Closer to Providence, laborers also sought work on the remaining farms in Johnston and Cranston, Rhode Island.

Cesar Lockwood was paid wages for nearly a full year from 1793-1794 cutting wood on James Arnold’s farm in Cranston

Israel Arnold would pay Sylvester Lockwood and others for work on his farm such as William Weeks (son of Bunny W.) who worked from April through July 1811 on a variety of tasks, including digging and heaping dung, heaping stones, and planting. Weeks as with others was mostly paid in corn or cider. Most of these laborers agreed to work “half the time at a rate of 13 dollars per month to be paid in corn or money to purchase corn, the other half at harvest time”.

Arnold had paid workers for some time . In the years from 1801 to 1811, he seems to have paid cash more liberally to laborers for a variety of tasks. Samuel Profit was paid 1 dollar and 2 shillings in 1810 for six months work. A woman only named as “Bessie” was paid 6 dollars for making clothes: “short trousers and sum other workshirts”, presumably for Profit and taken out of what wages he would have earned.

Cato Waterman was paid 3 shillings for pulling flax on July 27th and August 10th of that year.

Despite seldom rising above menial labor, people of color were persecuted and victimized by white laborers, especially in those heavily populated towns like Providence where independent black households continued to increase in the nineteenth century. These white laborers and their threats against the black and indigenous populations were supported by both politicians and the press.

On the evening of October 14, 1824, an attack began in the area of Providence dubbed “Hardscrabble”, a neighborhood of black owned and rented dwellings that had also seen white speculators build and rent to less desirable tenants. When a group of blacks resisted moving off a sidewalk to make way for a group of white revelers, the whites gathered outside the dance hall and dwelling of black resident Henry T. Wheeler. When a mob had been drawn to the commotion and gathered, Wheeler’s house was ransacked and eventually razed by upwards of sixty people throughout the night. Others in the mob went on to attack other houses and people, using clubs and axes, and lanterns to destroy some twenty homes and businesses

In the month leading up to the attack, the Providence Gazette had published an editorial condemning the recent influx of black emigrants to the city, and blamed them for a recent rash of “crime and mischief”. The editorial also advocated the colonization of blacks in Haiti. The defense attorney for those formally prosecuted for the mobs destruction told the jury

“…the renowned city of Hardscrabble lies buried in its magnificent ruins! Like the ancient Babylon it has fallen with all its graven images, its tables of pure oblation, its idolatrous rights and sacrifices…we must all agree the destruction of this place is a benefit to the morals of the community”. [i]

One of those whose homes were destroyed was Christopher Hill, a widower with three children who earned a living mainly as a woodcutter. In the months after the riot he refused help from neighbors and white philanthropists and lived with his family in the cellar of their ruined home, a remnant of the roof giving them some protection. The following spring the family left Providence for Liberia.[ii]

A second riot seven years later broke out on Olney Street and lasted through three days of brawling and destruction. By 1831, black citizens had raised a neighborhood on the west end of the street that was comprised of hard-working poor families. Closer to the city on the eastern end flourished a host of taverns, ballrooms and houses of prostitution where sailors of all color congregated, drank, and often brawled.

On the night of September 21, 1831, a fight broke out in a dance hall with a group of white sailors taking on a black man called “Rattler” who proved to be a skilled fighter, and when he had beaten the men, other patrons and sailors spilled onto Olney Street and continued fighting. The violence only ended the first night when black sailors drove the whites from the scene. The following night, a mob of whites returned to avenge the routing they had suffered. The mob succeeded in burning two homes but dispersed when fired upon by a black resident who killed one among them. Returning a third night, with anti-black recruits from neighboring towns, the black laborers who owned houses were given warning to leave, and then tore through the street, damaging houses, businesses, and banks.

It was only then that the State took action to quell the uprising, sending first, a paltry twenty-five man militia unit who were quickly sent fleeing from the scene. On September 24, the State sent in two companies of militia. Standing before them, a justice of the peace read a dispersal order from the Governor. When the mob pelted the justice and militia with stones, the soldiers opened fire on the mob, killing four and wounding others. The riot was finally ended, but the episodes highlighted, as historian Robert J. Cottrell would write

“of forces that were shaping a separate and inferior place in Providence society for blacks…Providence blacks found the law reluctant to extend its protection to them. In business dealings blacks were swindled out of money, labor and property while the law provided little redress”. [iii]

The Hardscrabble riot was certainly a factor in the decision Newport Gardner and of thirty-one other blacks who emigrated from Rhode Island to Liberia in 1826, just eighteen months after the riot. For those who remained, unity would provide the only protection against the oppression they now faced in the city and throughout the state.

An African Benevolent Society founded in Newport in 1807-1824, worked for the seventeen years of its existence to assist black families living on the edge of poverty, and to promote the formation of schools and education of black children. These schools, and later churches, were often constructed by donations from white supporters, both formal organizations and private individuals. White clergy in colonial Rhode Island also wrote of their success in ministering to the black population of their communities in segregated “bible studies”, as well as baptisms and visitation.

Postcard of the 1st Baptist Church in Providence whose congregation assisted black parishioners in beginning their own house of worship.

Long courted by Anglican and Quaker meetinghouses, most free blacks rejected those places where their ancestors had often been forced to attend, “pigeon-holed” in separate balconies or pews from their masters and families. Some attended Baptist churches-the enslaved held by Moses Brown did such before they were emancipated though he was a Quaker- and though blacks often found favor in such houses of worship, and were even encouraged to preach if they were found to have such a gift; such favor was limited to a handful of churches and meetinghouses in Providence and Kent counties.

Blacks then formed their own places of worship, the first such being the African Union Meeting House in Providence. The meeting to plan the black church was held in the First Baptist Church of Providence, partly because, explains Cottrell because the church leaders recognized that there were a majority of blacks who remained unministerial because of their refusal to attend a church where they remained segregated from the white attendees.

By contrast, when the new church was constructed and consecrated, “a parade to the new church included Quakers and other whites who had aided in the establishment of the black church”.[iv]

The Providence census of 1820 shows that the majority of those involved organizing the church were black heads of households, with children and young adults occupying those households. These families had raised some $800.00 out of their own pockets. For this reason, the African Union Meeting House was also utilized as a school for black children. The forming of the school and its policies were largely influenced by the Quaker donors to the church, having adapted the Lancasterian plan-a strict, corporeal form of education then popularly used by cities struggling to educate the poor among their populations.

The school opened under the leadership of a white Headmaster, charging parents $1.50 per quarter for tuition. Despite the cost and the cramped classrooms, 125 students initially enrolled. But the school faced difficulties almost from its inception. The Headmaster left after serving only a year, and the school was shuttered while looking for another. Teachers were also hard to find, and the school often found itself reduced to hiring itinerant teachers who would serve for a short duration and then depart. In time, two black itinerant preachers named Asa Goldsbury and Jacob Perry were hired to teach the students[v]. Despite the stabilization of the school, attendance fluctuated with the economic concerns of families. By 1828 the city had recognized its responsibility to the children of its black citizens and opened the Meeting Street School. A second school named the Pond Street school was opened in the community in 1837.[vi]

Itinerant black ministers would become both evangelists and activists in the forming of other organizations that worked for the uplifting of their people. Nathaniel Paul was an early organizer and fund raiser for the church, and the forementioned Asa . Goldsbury was described as an “octoroon”, often mistaken for being white. He had come to Providence from a church in Woburn, Massachusetts upon the opening of the black church in Providence.

In 1821, the dedication of the African Meeting Union House was attended by the African Grays a militia unit formed by self-titled Colonel George Barret, a veteran of the War of 1812. The Grays enlistees provided their own muskets. They mustered regularly and marched in regional military parades with other private militia units.

Their role was not just ceremonial however, their members were part of the black militia that helped to subdue the Dorr Rebellion.

Advertising image for convention of the Prince Hall Masons one of the first black labor organizations to advocate for black workers inclusion in the American work force.

A chapter of the Prince Hall Masons was formed in Providence as well. This organization paralleled the prestigious white organization popularized during the American Revolution, and like the revolution, began in Massachusetts with chapters spreading elsewhere in the 1830’s.

The Reverend John Lewis would form The Providence Temperance Society in 1832, further aligning black societal organizations with black churches efforts to instill self-improvement among its members. Lewis succeeded in obtaining 200 pledges for temperance from members of the black community. His dedication to the improvement of the black community in Providence included the opening of an Academy for black students in 1836, and in that same year, a “Convention of People of Color for the Promotion of Temperance in New England” a successful event that brough blacks and empathetic whites together.

In the wake of the Hardscrabble and Olney riots, authorities tightened laws on all manner of vices popular in the city taverns. An organization of white leaders and wealthy families formed the Providence Society for the Encouragement of Faithful Domestic Servants, modelled on similar organizations begun in England and more recently formed in New York, Boston, Philadelphia and elsewhere that were based upon a reward system of servants earning bonuses for faithfulness, frugality, and job performance.

A report on the shortage of domestic workers in the town lamented that

“It is supposed that there are servants enough in this town, to do the work of twice its population, and yet it is well known that good servants were never more wanted. This supposition is founded in part on the last census. As for instance, it appears that of the colored population, there is rising of twelve hundred in this town alone, yet only five hundred are returned as being at service. The seven hundred, except children, if they work at all are doing “days work”.[vii]

Notwithstanding the occlusion from mills, mercantile, and other establishments which resisted hiring black workers, the report complains that such workers resorting to day labor are often reduced to “habits of idleness and dissipation”.

Despite a great deal of organization. And the hiring of field agents to track subscribers progress, the organization ceased functioning in its second year.

The founding of the Providence Shelter for Colored Orphans in 1838 began an effort by wealthy white women who desired to “provide a suitable home where the children might be placed and taught habits of industry, improve their morals, and be instructed in such branches of knowledge as would enable them respectable maintenance as domestics in families, or to acquire trades adapted to their capacities or inclination”. [viii]

The shelter also struggled in its mission, able to only train and send eight children out as domestics of the sixty-four children received into the shelter during its first four years. While providing resources for many poverty-stricken or dysfunctional families it served as part of the “benevolent society” so sought in the 1830’s and 40’s by progressive Americans.

Ultimately, the descendants of the enslaved would be those that built the foundations for their children and grandchildren to rise above the further marginalization caused by the economic recessions of 1837 and 1839, and the continued divisions that carried the nation into civil war. For even as the Rev. John Lewis was finding favor with whites, and funding for his advocacy of temperance and self-improvement for blacks in Providence, the idea of the education and advancement, no less the subject of enslavement itself was still an uneasy subject in South County.

In February 1841 in the Meeting House that Daniel Stedman attended, a debate ensued upon “whither intemperance of slavery is the greatest eavle (evil)”. After “a Debate of 2 Evenings” with “A great number of arguments on Both Sides”, it was decided that “intemperance was the greatest eavle”.[ix]

The following month, no doubt hearing of the debate, an unnamed man “came to Lecture on Slavery”, but the church objected to holding such a lecture in the meeting house as “Some was not willing (to listen) and the rest did not want to hurt the other’s feelings”.

The unnamed abolitionist left without having been heard. “…he went off”, Stedman writes, “and did not Lecture them”.

[i] Cottrell, pp. 54-55

[ii] Ibid.

[iii] Ibid., p. 57

[iv] Ibid, p. 59

[v] Ibid. p. 62

[vi] Ibid, p. 61

[vii] Lancaster, Jane Encouraging Faithful Domestic Servants: Race, Deviance, and Social Control in Providence Rhode Island History Vol. 51, Number 3 August 1993

[viii] IBID, P. 83

[ix] Fletcher, Daniel Stedman’s Journal, pp. 188-189

[i] Hazard Caroline, Nailer Tom’s Diary or The Journal of Thomas B. Hazard of Kingstown, Rhode Island 1778-1840 Boston, The Merrymount Press 1930

[ii] Ibid, p.116

[iii] Ibid, p.117

[iv] Ibid, p.253

[v] Ibid, p.123

[vi] Ibid, p 619

[vii] Fletcher, Cherry Bamberg (ed.) Daniel Stedman’s Journal Rhode Island Genealogical Society 2003

[viii] RIHS Mss. 459, 1786-1830 E&C Greene Accounts and Ledgers

[ix] Sambo would later lead an uprising of black workers against Updike cousin Daniel Eldred Updike, the Wickford harbor master on January 28, 1809. Both able-bodied seamen and dock workers had lost employment with the embargo of 1807. Harbormaster Jeremiah Olney in Providence and William Ellery in Newport sought to crack down on the resultant smuggling along the coastline. The passage of an Act against smuggling by state authorities coupled with the seizure of the sloop Betty in Pawtuxet, from where she was towed to Providence harbor seems to have set off a series of violent assaults on docks and property along the coastline, including Wickford. See Strum, Harvey Rhode Island and the Embargo of 1807 Rhode Island History, Vol. 52, no. 11, p. 59

[x] RIHS Mss. 459, Box 1, Folder 11 Accounts 1810-1814

[i] RIHS Mss. 770 Cases 2, 14 Updike Papers, Daybooks 1791-1804

[i] RIHS Mss. 483 sg12 series 2, Box 4, Folders 7, 14

[ii] RIHS Mss. 753 Box 1, Ledger 1

[i] The later location of the “Turk’s Head” building.

[ii] RIHS Mss. 9001 B. Box 1

[iii] Ibid.

[iv] Ibid.

[v] Cottrol, p. 48

[vi] RIHS Mss. 29 Vol. 25, 74

[vii] National Park Service, The Men Who Turned: African-Americans and the Slater Mill Story https://www.nps.gov/blrv/learn/historyculture/the-men-who-turned-african-americans-and-the-slater-mill-story.htm accessed 7/24/23

[viii] RIHS Mss. 29, Loose Vol. 4

[i] Rhode Island Historical Society Collections Mss 9001-G Box 8

[ii] RIHS Mss. 313

[iii] McBurney, Christian The Memoirs of Cato Pierce Rhode Island History Vol. 67, No. 1. Rhode Island Historical Society 2009

[iv] Ibid, P. 6

[v] RIHS Mss. 232 sg 4

[vi] RIHS Mss. 629 sg Series 8, Box 2, Folder 24: Asa Potter Sr. (1766-1805) Deeds, Agreements, 1802-1805

[vii] RIHS Microfilm, F89. N8, Reel 6

[viii] RIHS Mss 214, sg 1, Series 1 Vol. 6 No. 2745

[ix] RIHS Mss 214, sg 9

[x] Cottrol, p. 45

[i] Hopkins listed five enslaved individuals in his 1760 will, a man, a woman, and three children. See Bamberg, Cherry Fletcher; Hopkins, Donald R. (January 2012). "The Slaves of Gov. Stephen Hopkins". New England Historical and Genealogical Register. 33: 11–27. ISBN 978-0-7884-0293-7.

[ii] Stokes, Keith

[iii] Cottrol, Robert J. The Afro-Yankees, Providence’s Black Community in the Antebellum Era Greenwood Press 1982 p. 32