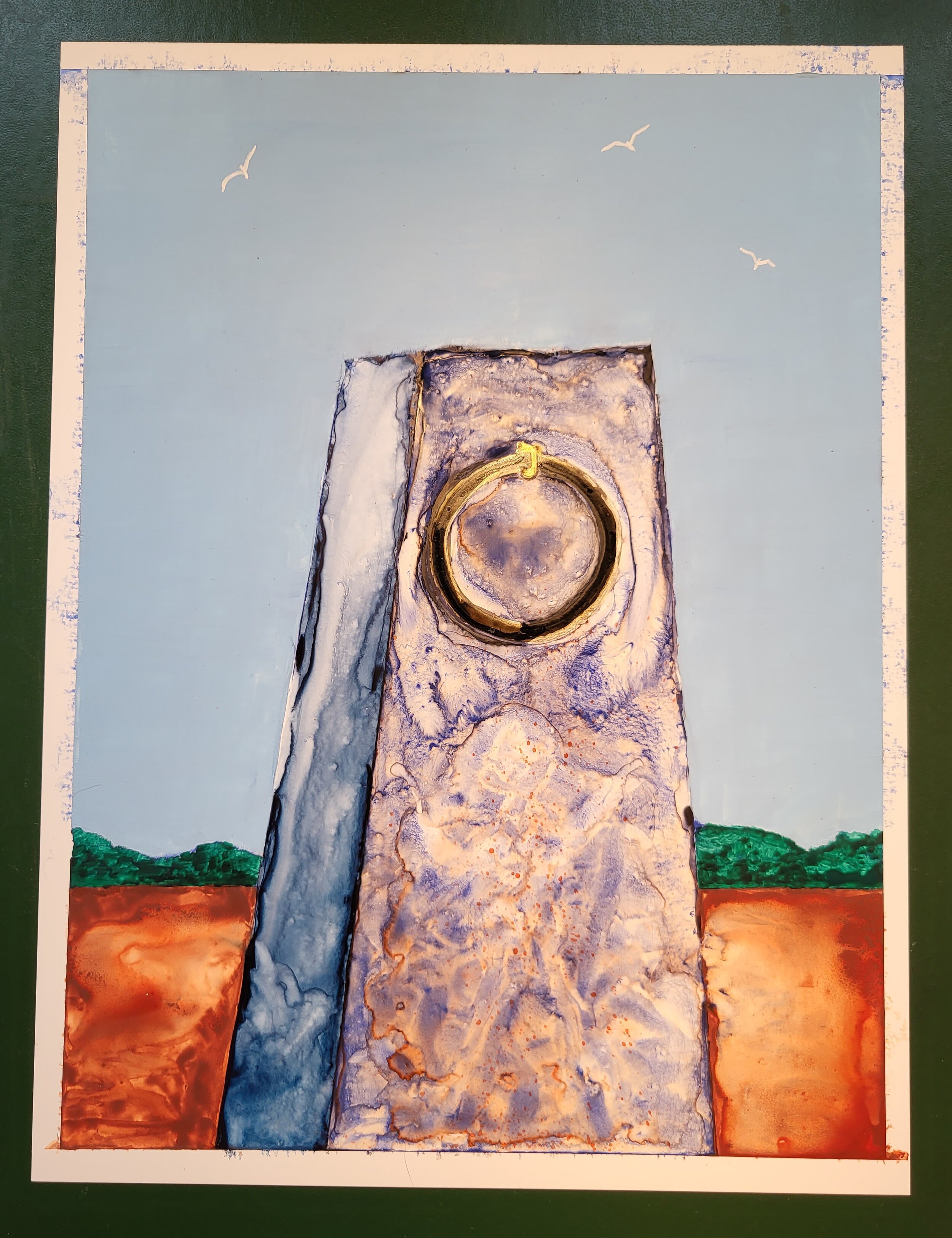

“The Whipping Post” watercolor on paper by the author. From a series presently featured in the exhibit “Anchored in Rhode Island”

In the early 1600’s, as English men and women were leaving England to come to the New England shores to begin colonizing that area let me tell you something that was NOT happening. William Bradford and others, as their ships of Pilgrims were weighing anchor in England and other harbors, did not look around, throw up their hands and yell: “Wait a minute! We need to take some lawyers!” America has always had a love/hate relationship with attorneys and it started at the very beginning. Today I want to talk about the development of that relationship in RI from the time of its founding in 1636 to just before the American Revolution - which according to John Adams began in 1760. I’m going to tell this story by referencing two men, Roger Williams and Daniel Updike, Esq. whose work in RI intertwined in developing RI’s unique version of The Law.

From 1636 to 1757 this area we call Rhode Island, had three groups of peoples living here, trying in one way or another to create a society they could at least endure. There were indigenous tribes, enslaved africans, and immigrant europeans (mostly from England or who considered themselves “English”). The law that developed here - whether it happened by force of argument, will or violence was created by the immigrant English for all inhabitants - everyone had to abide by it but Africans and indigenous tribes did influence how that law was shaped. However, it was seldom shaped in their favor. I’m going to give away the plot of this story at the beginning. To have a smoothly functioning government and economic “engine” it requires a fair amount of “grease”. Law and Lawyers provide that grease. To put it another way: ‘There is no law without lawyers.” [Nathan Roscoe Pound - most cited legal scholar in the 20th century. Dean of Harvard Law School 1916 to 1936.]

It has been said that two conditions are necessary for the rule of law as we understand it today.

“Firstly, a class of professional - expert, skilled and properly trained - lawyers cannot possibly flourish until there has been developed something resembling a distinct and consistent body of laws, a distinct and consistent procedure, and a settled jurisdiction, including regular courts manned by a trained and competent personnel.

Secondly, the society in which the lawyer works or intends to work must, to some degree, accept him as a professional man, call for his professional services and generally honor and respect him as well as permit him to find his livelihood in the practice of law.” [I would note that’s a quote from a 1957 law review article, hence the shocking lack of reference to females in the law.]

English colonizers in North America brought with them some familiarity with what was being called the English Common Law. They didn’t always approve of it. Puritans and Quakers were very skeptical having been, in their opinion, badly used by the King’s law and lawyers in England. And the colonies didn’t have a whole lot in common initially.

~ the colonies were formed at different times, founded separately, had different foundational goals, principles and purposes.

~ no common policy

~ no parallel development

~ each had its own form of government

~ each had very little contact with the other

~ each had different geographies, different European immigrant groups, different indigenous tribes, different groups of enslaved Africans, different climates, different economic strategies, even different social groupings within the “English” immigrants.

~ You could fairly argue that some of these differences are still present in this country and still provide a challenge to the rule of law. That’s another subject.

Sir Edward Coke (1552-1634) Responsible for the US Constitution’s 4th Amendment protecting Americans from unreasonable government searches and seizures. Roger Williams clerked for this famous English judge and legal scholar who is credited with the foundation and development of English Common Law, judicial record keeping, and the idea of “precedent” (of judicial prior decisions shaping future decisions). Roger Williams was a well educated man by the time he came to the colony of Massachusetts, maybe too well educated for their taste, and ended up in what would become the RI colony in 1636.

RI was pretty small potatoes in 1636. Its initial population just a few hundred “English”. By the time Roger Williams had died in 1683, the colony still had just four primary towns (Newport, Providence, Portsmouth, and Warwick) and just over a 3,000 non-indigenous population [“English” and “African/African American”].

Roger Williams like many of those trying to create a law abiding society, generally felt that the New World represented new situations and the English Common Law could be a guide but had to be freely adapted to the new surroundings. That was an argument that continued until after the American Revolution.

“Their colonial charters provided that all colonial law must conform to English law, but deviations began to appear in several areas almost from the first moment of colonization.” from Law America by Sally Hayden, Western Michigan U. (2018)]

In 1637, the men of Providence (for themselves and their families) signed a Compact where they all agreed to obey “…all such orders or agreements as shall be made for public good of the body in an orderly way, by the major consent of the present inhabitants, masters of families incorporated together in a Towne fellowship, and others whom they shall admit into them ONLY IN CIVIL THINGS.”

By 1640 they amended the original compact, moving further away from a “pure democracy” by agreeing that there would be five men selected from among the inhabitants called “disposers”, i.e. people who could legally make “dispositions of land, stock and all general things.” The plan for government was a “government by way of arbitration” and a Town Clerk to keep records. Records which were likely destroyed in during King Philipps War and the sacking of Providence. Portsmouth and Newport and Warwick had similar compacts which were modified every few years. Until 1644 when the Parliamentary Charter for RI was created. That more formally drew the 4 towns together.

In these early days of the colony many disputes were disposed of within each of the four main towns. Churches and merchants served as arbitrators and mediators to resolve problems because there were so few trained lawyers and judges (I.e. anyone with legal training.)

A downside to the four towns being so loosely connected as a political body is found in this example. In 1652 Providence and Warwick passed a law forbidding slavery of any person, including indigenous and blacks. However, Portsmouth and Newport (where the “slave” trade was already becoming an economic benefit for them) failed to do so. The 1652 law was ignored and in 1703 slavery was officially recognized in the colony.

Just a short word on the formal charters RI functioned under until they wrote their first Constitution in 1842.

~ Charter of 1644 gave RI the authority to exist as a colony. Incorporated the 4 original towns. Was a Parliamentary Charter (not granted by the King - Charles I had fled power, no monarch).

~ Royal Charter of 1663 - King Charles II on the throne in 1660 - entitled: “The Governor and Company of the English Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, in New England, in America”. RI became the first and only colony allowed to elect every governing official, including Governor.

~ 1686 to 1688 King James II revoked all colonial charters from New Jersey to Maine called the Dominion of New England under one appointed governor. Thankfully, James II was forced to abdicate the throne, the governor was arrested in Boston and all those colonies returned to their prior legal state.

In RI, as in most of the English colonies, most men holding themselves out as attorneys had no professional training, no experience in practicing the law; and were held to no ethical standards. As one legal historian has said about them: “Those who acted as attorneys or lawyers were overwhelmingly sharpers, spellbinders and pettifoggers; and they frequently stirred up litigation solely for the sake of fees. It was the sharp trader or the clever land speculator, the man of easy penmanship and clever volubility who, as a rule, ‘practiced law.’” (p. 59 — “Legal Profession in Colonial America” law review article). Here are just a few of the things that hampered the development of lawyering as a respected profession in the colonies:

~ no college level lectures on the law given before 1780

~ no law schools before 1784

~ hardly any printed material available for study

Five ways you could become a Colonial lawyer:

1. By your own efforts, gather whatever scraps of legal information you could, mostly a few books in private libraries. 60% of male population considered “literate” meaning able to read, fewer could both read and write.

2. Serve as a scribe, copyist or assistant in the clerk’s office of some court, as check into those books in private libraries.

3. Enter the law office of an experienced attorney (hopefully with a law library); prepare pleadings, other legal documents, attend court and make notes.

4. Go to England and become a member of one of their four Inns of Court. About 30 to 40 men sought this method of becoming a lawyer before 1760. None from Rhode Island.

5. Attend a college in one of the colonies and then do numbers 1-4.

As we get into the early 1700’s the need for better legal training in a growing economy became apparent. As RI entered into the International Slave Trade, their merchant politicians recognized the law and lawyering in RI needed improvement. That brings me to Daniel Updike, longest serving attorney general for the RI colony at 24 years.

He was tutored in his father's house here at Smith’s Castle. As a 21 year old [1715] he went to the island of Barbados - where family and business connections lived and worked. Barbados was a very active part of the International Slave Trade. In 1661, Barbados became the first English colony to pass a comprehensive slave code. When Updike returned to RI a year later his knowledge of those laws would be important as RI needed to create its own version of Black Codes to deal with their trading and control over domestic enslaved Indigenous and Africans. RI colonists had to create legal explanations for their ongoing enslavement of Native Indians and then Africans and African-Americans.

Black Codes were a fairly dramatic example of how the English Common Law had to be reworked ignored to justify the enslavement of entire groups of people and to manage them within colonial society. In 1703 the RI General Assembly adopted an early, what they called, “Negro Code” to restrict the activities of FREE and SERVANT Negros and Indians. One of the interesting aspects of this is its application to ALL people within those two groups. Free or Enslaved - these codes applied equally.

An example: “If any negroes or Indians either freemen, servants, or slaves, do walk in the street of the town of Newport, or any other town in this Colony, after nine of the clock of night, without certificate from their masters, or some English person of said family with, or some lawful excuse for the same, that it shall be lawful for any person to take them up and deliver them to a Constable.” (1703)

A very important phrase in that law is “lawful for ANY PERSON to take them up”. This law, like all the Black Codes did two very important things that would have lasting consequences down to today: (1) it criminalized entire groups of people based on appearance and background - not on individual acts; (2) it required the participation of the entire “English”/white population to act as enforcers of these laws. So regardless of your personal views on enslavement, you were required to ensure the laws were applied. Failure to do that could result in legal repercussions for you.

An example of that was in 1714, RI enacted a law prohibiting ferrymen [a very important way for people to travel within and out of the colony, from transporting an enslaved person [i.e. anyone who looked like they could be enslaved] “without a certificate in their hand from their master or mistress or some person in authority.” And, of course, one way to keep laws like this enforceable was to restrict the teaching of reading and writing to the enslaved.

When your economy requires enslavement to function you have to restrict the activities of the enslaved. Everyone knew being a “slave” was a bad thing, something to be avoided and fought against. If you don’t believe me, read anything written in the colonies leading up to the American Revolution. They rail against being made “slaves” by the King and/or Parliament. They knew the enslaved would try to find ways out of slavery. Hence laws like this passed in 1750 preventing “all persons keeping house within this Colony from entertaining Indian, Negro or Mulatto slaves or servants.” Again, a law forcing freemen (English/white) or freedmen to enforce the Black Code.

Parenthetically, its in the early to mid-1700’s that words like “mulatto” begin to appear as the population of enslaved begins to include more and more people born from white/black parentage - usually, white fathers and black/indigenous mothers.

In 1722, at the age of 28 Daniel Updike wins his first election as attorney general for the colony. In 1723 he’s directed by the General Assembly to collect delinquent fees on imported enslaved Africans. He got to keep 10% of whatever he could collect as well as 5 shillings for ALL imported enslaved.

In 1729 he and three others were appointed to a committee to revise and print the laws of the colony. First compilation of RI’s laws published in 1719. But not organized. Redone in 1730. Digest and Supplement in 1745, printed by the widow of James Franklin, brother of Benjamin. It would not be until 1750-55 that a bound collection of the legislative actions of the General Assembly were published. Updike and others felt this hard to come by books limited the growth of the legal profession.

In 1730, he was one of the founders of the literary institution in Newport, later known as the Redwood Library. Between 1741 and 1763 the library was built with the participation of enslaved and free African skilled labor.From 1741 to 1743 he was an attorney for Kings County (now Washington County), and during the same time he was appointed on a second committee to revise the laws of the colony. He and others recognized that a lack of legal materials held back the development of new lawyers and judges and apparently had his own extensive law library. Sadly, at this time we only have one volume of that, a law dictionary.

He was attorney general for two periods of time: 1722 -1732 and 1743 - 1757. In between he had a very active private practice, involved in over 250 civil cases. In the 1720’s civil litigation increased dramatically. Most cases were economic inn nature, especially debt collection. In 1736 he signed on to a petition attempting to help create and protect those trying to make a living full time as attorneys. The “petition was brought by ‘all who are that deserve the name of attorneys in the colony’ and ‘Practicers of the Law.’ The attorneys sought to limit the practice of law in the colony to RI residents so that attorneys would be ‘the more desirous of a just and faithful exercise of their calling to the good of mankind in general.’ Economic concerns were the motivating factor for the petition. The attorneys wished to ensure they could make a living from the practice of law … and wished to exclude additional outside practitioners - primarily from Massachusetts Bay. The petition was unsuccessful.” [ p.30 law review article] (Most states still have in place some restrictions on attorneys coming in from other states/jurisdictions to practice in RI. Still an economic issue.)

From 1636 to 1760, RI (like most of the English colonies of NA) gradually created a unique legal system. They carried over what they liked from England but made changes (for good or bad) based on their unique situations.They went from being very skeptical of “The Law and Lawyers” to deciding they were a very necessary part of government and the economy and slowly developed lawyers and judges into a separate profession. But by March 22 of 1775, Edmund Burke a noted member of Parliament and legal scholar of the time said this about Americans and their “study of the Law” on the floor of the House of Commons:

“In no country perhaps in the world is the law so general a study. The profession itself is numerous and powerful; and in most provinces it takes the lead. The greater number of the deputies sent to Congress were lawyers…. This study [of law] renders men acute, inquisitive, dexterous, prompt in attack, ready in defense, full of resources… they anticipate the evil, and judge of the pressure of the grievance by the badness of the principle. They augur misgovernment at a distance; and snuff the approach of tyranny in every tainted breeze.”