Above portrait of Henri Christophe by Richard Evans 1816

I have spent much of the last decade writing of and giving talks about Rhode Island’s historic attempt to raise a “Black Regiment” that would serve in the War of Independence.

The Act of the General Assembly in February 1778 was historic because it was the first attempt to raise such a force of enslaved men in America, though free blacks and other men of color had enlisted in previous wars and militia. Lesser known is the regiment of black soldiers who served with the Lègion de Lauzun of France.

That year of 1778 also was the beginning of the important alliance with the French government, one that assuredly increased our chances of winning independence from Great Britain with much needed “money and material” as well as both naval and military support.

The alliance however, began in disarray when after weeks of naval battle with the British Fleet, the French ships off Newport were battered by a hurricane and retired to Boston for repairs during the attempt to wrest Rhode Island from British hands. Without the French fleet or soldiers to support troops, the already stalled campaign fell to a day-long skirmish with Hessian troops before a retreat off the island.

The resultant anti-French feelings among American commanders caused the fleet under Admiral d’ Estaing to sail to the Caribbean, where he spent much of 1779 playing cat and mouse with British vessels and recruiting militia from the islands. He also successfully launched an attack that captured Grenada, but by August was recalled to North America to provide support for the siege of Savannah.

D’Estaing arrived in Charleston harbor on September 3, 1779 with his fleet of 33 warships, equipped with 2,000 guns and holding an army of 4,450 men. Among these were a group of some 941 men of color recruited from the Islands of Guadeloupe and Granada as well as other “Mulattoes, and Negroes, newly raised in St. Domingo[i].“

These Chausseur-Volontaires had a long history on the island. Both free blacks and free mulattoes served in the militias and the marechasee’, the rural police force.[ii] Still, in their own native land they were forbidden to ride in coaches, become midwives or surgeons (physicians), or even to travel to the mainland, less the “purity and beauty” of the French nation be “disfigured.”

The Chasseurs arriving with d’Estaing were called the Fontanges Legion after their French commander Major General Viscount Francois de Fontanges, and included numerous men who would become famous in the later Haitian Revolution, including twelve year old Henri Christophe, the future king, Henry I.[iii] The young Henri was signed on as an orderly to a French naval officer.

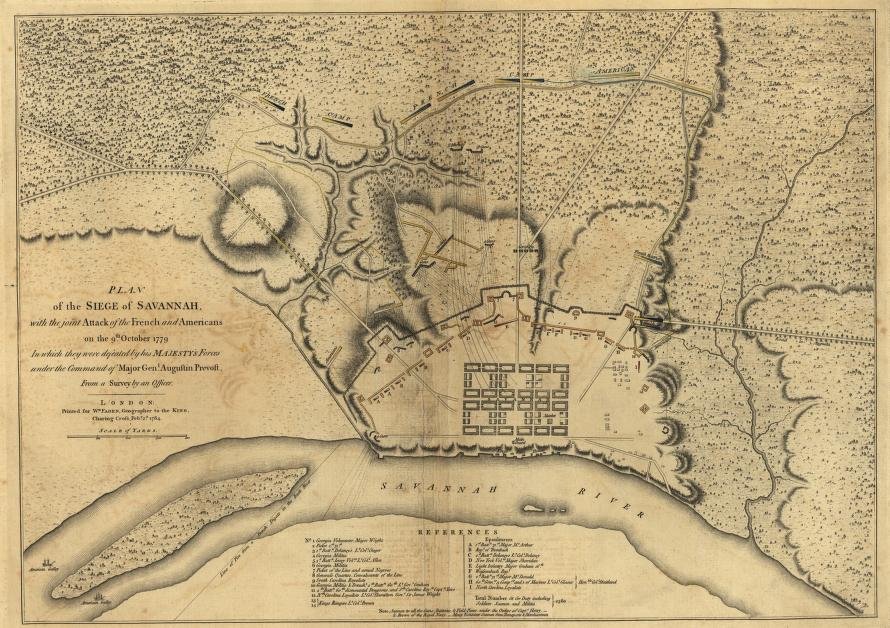

On arrival, three divisions of the French Army joined the 2,100 men under Major General Benjamin Lincoln, and set up separate encampments along the Savannah River. Another large contingent of French troops and 545 of the Chasseurs were landed on Tybee Island for a siege on the British outpost there.

Initially, the French did much damage to the British fleet, capturing the warship Experiment and her 50 guns, as well as the frigate Ariel and two store ships carrying the payroll for the Savannah garrison, and Brigadier General George Garth, who had been scheduled to take command of the British forces in Georgia on his arrival.[iv]

On land, the Fontanges Legion scouted the British fortifications on 8 September. A few days later, the off-loading of cannon and mortars some five miles from the siege site began in a heavy rainstorm on the night of 11 September. The remainder of the French troops began landing at Beaulieu, on the Vernon River that night. They unloaded more artillery that would have to be hauled fifteen miles to their emplacement. The British meanwhile, continued to build fascines and fortify their defenses on the mainland. They sank six of their ships in Savannah harbor to blockade the French fleet from getting close to shore and bombarding the city beyond the garrison.

Lincoln moved his men south to Cherokee Hill, just west of Savannah by 15 September. On the following day d’Estaing wrote to the British Major General Augustine Prevost, demanding the surrender of the city. Given twenty-four hours to respond, he delayed replying as he knew reinforcements were arriving soon with 800 regulars from the garrison at Beaufort, South Carolina under Col. John Maitland, and the 1st Battalion of de Lancey’s brigade from Sunbury under command of Colonel John Harris Cruger.

Provost chose a redoubt built upon Spring Hill, off the southwest border of the town, as his strongest position of defense.

With his manpower significantly increased, the Major General declined to surrender, and instead sent out a sortie of some 200 regulars on the morning of 17 September to attack the French battery near the barracks. The British were repulsed and pushed back into their own redoubts with the loss of 53 men killed, including their commander, Col. William Campbell, and two other officers. Another 100 British regulars were wounded.

The French too suffered the loss of twenty-six men, and the wounding of 84 soldiers, including ten officers; largely the result of British cannon fire during the counter attack on the redoubts.

The following day, the Continental troops sent the Legion of recruits under Brigadier General Pulaski, and members of the 1st Regiment Continental Light Dragoons to stake out any movement of troops or supplies to Ogeechee Ferry, and that day they trailed and overcame a party of Loyalists driving a large number of “horses, cattle, and Negroes to St. Augustine.”[v]

Pulaski’s troops captured 50 men, along with livestock and slaves.

Sorties continued in the coming days from both sides. On the night of the 22 September, a regiment of fifty grenadiers under Lieutenant M. de Guillame of the Viscount de Noilles division launched an attack upon a British outpost five miles from the city at a place called Thunderbolt Bluff. Rather than take the post by surprise as instructed by the Viscount, Lieut. Guillame drove his force in a head-on attack that was easily repulsed; leaving six men killed and several wounded with the first volleys. Supporting troops had little choice but to retreat.

The following day, the siege of Savannah began in earnest. The French and American forces began digging trenches and preparing to bring the artillery into place. A British sortie on the newly dug trenches the following day resulted in the loss of seventy Frenchmen killed or wounded. The attackers had lost little with four killed and fifteen wounded by comparison. The allied soldiers persevered, getting cannon into place along the siege line by 3 October, and the bombardment of the town from land and sea began the following day.[vi]

The bombardment last several days, utilizing 10 mortars and some 54 pieces of heavy artillery. Provost had pulled down his barracks and used the wood to construct a large and formidable battery. As the bombardment continued, some French gunners fired into their own lines. They were reprimanded when found to be drunk, but continued the assault with little improvement in accuracy.

The Allied plan had been to weaken the British defenses with the bombardment, finish the trench lines, then by a systematic approach, make an assault upon the town. News of coming bad weather hastened d’Estaing to prepare for an immediate attack. Brigadier General Lincoln begrudgingly agreed to bring up his 5,000 troops and prepare them for battle.

The plan then became to launch a two-pronged assault on the Spring Hill redoubt, a formidable task. A line of smaller redoubts and earthworks connected with the main post, and dense swampland protected the western flank of these defenses. In addition, the British had the brig Germain anchored with her guns in the Savannah River to provide enfilade fire along the allies northwest flank.[vii]

Around 4:00 a.m. on 9 October, the allied plan was put into motion. Five hundred South Carolina and Georgia militiamen under Brigadier General Isaac Huger began the assault with a diversionary attack on a redoubt at White Bluffs road, manned by troops under Lt. Colonel John Harris Cruger.

The French troops under command of General Arthur Count de Dillon planned to emerge from the swamp in a secondary assault but became lost, and then bogged down under a blistering attack from the entrenched British forces. While in this weakened condition, British marines and grenadiers charged, leading to fierce hand to hand combat in which many of the French grenadiers were killed with bayonets. The Viscount de Castries later reported that “in less than half an hour more than 2,500 men were killed on the spot.”[viii]

D'Estaing was wounded in the leg, attempting to regroup French forces. This resulted in further losses when a column under Col. Lachlan McIntosh were diverted into Yamacraw Swamp where they came immediate fire from the guns of the Germain.

The South Carolinians, Georgians, and French cavalry fought “a long and bloody battle in the ditch outside the Spring Hill Redoubt.” The allies pressed the assault three times in an effort to gain the parapet but were repelled each time. The assault led by General Pulaski and his two hundred cavalry led to his death, and d’Estaing was wounded in the leg while trying to regroup his forces. After these efforts, Lincoln retreated his forces, and the Fontanges Legion stationed as the rear guard, “fighting the English troops with obstinacy and boldness”, prevented the allied forces from annihilation.

The Americans lost approximately four hundred and forty-four men. Eighty dead were found in the ditch below the redoubt, and another 93 on the battlefield outside the trench.

The French dead included a significant number of the Fontanges Legion. Another 650 of the ranks were wounded in the battle.

Following the defeat, d’Estaing and his troops boarded their ships on 20 October and departed once again for the West Indies. Some units of the Fontanges Legion were taken to support garrisons at Grenada and St. Lucia.[ix] Others remained with Major General Lincoln, tending to the wounded as he marched the remainder of his troops back to Charleston. Those wounded in the battle, including Henri Christophe and Martial Besse were returned to St. Dominigue.

Of these surviving Chasseurs, a significant number would contribute to their own Revolution.

Among them, Jean-Baptiste Mars Belley would become an important leader as a delegate for his people, especially those enslaved as he had once been. As a young man, he had been sold into slavery from Senegal and spent the rest of his life, both enslaved and as a free man in Cap Francais, a bustling port and market town surrounded by numerous plantations. Though not the capital of the Island, the city was the seat of the governor, and held a large government compound, a large hospital, a parish church with an impressive colonial colonnaded façade, and several squares with elaborate fountains. A eighteenth century writer termed it the “Paris of the Island.”[x]

Saint Domingue was the wealthiest of the colonies in the Caribbean. The three regions of the Island,: North, West, and South were abundant with sugar and coffee plantations, as well as farms that grew indigo. In Cap Francais, there were also more than one hundred jewelers working in gold or silver for the market. The grande blancs, or wealthy white planters often held enslaved people in excess of their needs. Such was their need to show off their status that an entourage of enslaved paraded with them or their mistresses through the streets whenever they entered the town.[xi]

In this sophisticated urban setting, Belley mixed in with the many other urban enslaved who labored as drivers of coaches or wagons, filling barrels of coffee or sugar to be rolled to the wharves, others worked on the docks or in the holds of the ships as carpenters and mechanics.

Belley was also literate and well read. By 1777 he was enlisted with one of the five black militia units associated with the city, and part of a military leadership group who formed an important, if not symbolic presence in the community. As historian Christine Leveque notes:

“…blacks associated with the military not only knew each other but formed a kind of pseudo-kin family that provided support and also participated in many of the other members important life events. They acted as godfathers at baptisms, witnesses at marriage ceremonies, mourners at funerals, and cosigners of manumissions and other economic transactions.”

Belley participated in at least fifty of such ceremonies. These acts of support and solidarity, she argues, kept them separate from the white and mixed-race world.

On his return to St. Domingue, Belley worked with other veterans of the Chasseur-Volontaires to improve their status at home. The alliance with American troops had surely changed the way they viewed their lives. As Leveque points out,

“The values of freedom, patriotism, and civic virtue had now been placed in a context of international and interracial collaboration, even as he was constantly reminded that he served at the whim of white officials.”[xii]

It is entirely possible as well, that word of the American’s offer of freedom to blacks who served in the Continental Army had made newspapers in Paris, that were passed along to the population in St. Domingue before the Fontanges Legion had been formed.

In March 1780, the Governor of St. Domingue put out orders that a new unit, the Chasseur Royaux, would be formed. Service would no longer be voluntary, but young men from each parish would be conscripted to serve. The plan met immediate resistance. The Captain of a mixed-race militia in Le Cap wrote to the Governor in no uncertain terms that the Chasseurs were “…free men who have the ability to choose the Company in which they will do their service.” Conscripts for the new unit refused to enlist, and long-standing officers of the Chasseurs issued a complaint to the Crown. The measure was soon abandoned.

Through the tumultuous decade that followed, Belley and other veterans of the American campaign continued to fight against oppressive measures in their homeland, which only worsened with the advent of Revolution in France.

In 1788 when King Louis XIV had issued a call for representatives from the Empire, planters in St. Domingue quickly worked as a collective of white colons to exclude citizens of color from political life. Nine white delegates thus represented the Island when the General Assembly met in Paris on 20 June 1789.

As events erupted in the capital that summer, the white colons attempted to consolidate their power. Fearing that the Assembly would raise the issue of slavery, the planters worked with the King’s deputies in his final months as ruler, to approve the formation of assemblies in the colony; which would of course be wholly tied to the interest of white planters, big and small.

In August as the National Assembly in Paris moved to create a Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, free men of color in St. Domingue were organizing their own advocacy, creating the Société des Colons, declaring their equality with the white planters who sought to oppress them. The Société still had to select a white spokesperson, the attorney Etienne Louis Hector Dejoley to address the National Assembly on their behalf.

On 22 October 1789 a delegation appeared before the representatives in Paris as their spokesmen read aloud the statement the free blacks had composed:

“There still exists in one of the lands of this Empire a species of men scorned and degraded, a class of citizens doomed to rejection, to all the humiliations of slavery: in a word, Frenchmen who groan under the yoke of oppression.”

Still, these were free blacks who were arguing for representation. The following month the Assembly heard from a group of enslaved blacks, issuing their contention that as “pure blacks”, not of mixed race as with many of the Société Colons, deserved not only their freedom, but a status above those of mixed race.

The advocacy by both groups only heightened the efforts of whites to prevent black citizens from gaining legitimacy. When the Credential Committee of the Assembly put forward a report favoring the free black request, members were pressured by the white colon, and the report was never presented to the full Assembly.

A massive and damaging slave uprising in the southern region of the Island in 1791, prompted the French, now under a constitutional monarchy to make concessions to the previous demands. On 4 April, 1792, the new Legislative Assembly voted to extend citizenship to all free people of color. Three commissioners and a regiment of troops were sent to distribute the order, quell the riots, and restore slavery to the plantations that had been destroyed in the revolt. Even as these commissioners landed on Saint Domingue, the revolution in France continued to evolve. Just days after their arrival, the Legislative Assembly of which they were part, was dissolved; and replaced by a National Convention that declared France a Republic.[xiii]

Among the commissioners that had arrived from France was Léger Félicité Sonthonax, an idealist lawyer who had embraced the revolution and would have an impactful role on men like Belley who sought equality in their society. In Paris, Sonthonax had joined the Jacobian club, a social male salon of delegates from the National Assembly which became increasingly more radical and progressive. In his own writings, the attorney wished for “a torrent that will sweep away the old abuses, and that a new order of things will rise…Yes!”

He foresaw the day when “we will see an African…without any other recommendation than his common sense and his virtue, come to participate in lawmaking in the midst of our national assemblies.”[xiv]

Those ideals would be tested, and reach some fruition with a handful of measures, first freeing blacks who had fought for the Republic, and then in June 1793, issuing a general abolition, and ordering the election of representatives from the local assemblies.

On 24 September 1793, Jean-Baptiste Mars Belley, or “Citizen Belley”, was the first to be elected a representative to the National Assembly. Five other deputies were elected, among them two black men, two whites, and one of mixed race.

Belley and the other delegates who had travelled with him to Paris were admitted to the National Convention on 3 February 1794 with open arms. Representatives rejoiced that the “old Aristocracy of the skin” had given way to liberty and equality. The following day, the Convention abolished slavery in all the empire’s remaining colonies.

The young Henri Christophe’s life paralleled Belley’s in many ways. Born to an enslaved woman and a freeman in Granada or St. Kitt’s, Christophe was brought as an enslaved boy to Saint Domingue’s northern region.

After his participation in the battle of Savannah, he was returned to St. Dominigue to recover from his wounds. He may then have worked as a waiter, or billiard marker at a hotel in Cap Francais, a later popular story told of his skill in dealing with wealthy clientele. Christophe earned enough income to enable his sister to join him on the Island as a free black, where she later married and raised a family. He was also a freeman by the time of the enslaved uprising of 1791 when he, like Belley; was part of the local militia.

Christophe is said to have distinguished himself as an officer during the years of revolution, and fought in numerous battles in the northern region under leader Toussaint Louveture. He was reputedly promoted to Commander-in-Chief of the forces at Cap Francais after Louveture seized power in 1801 and then to General shortly before Louveture’s deportment the following year.

He continued fighting under General Jean-Jacques Dessalines against the 20,000 French forces sent to restore order under the brutal Vicomte de Rochambeau.

Donatien-Marie-Joseph de Vermer Vicomte de Rochambeau, son of the Commander who had led the French forces that aided Americans in their Revolution, had actually been an aide de camp to his Father; arriving in Boston on the frigate Concorde on the 8th of May, 1781[xv]. He would spend a little more than a month at the encampment in Newport, Rhode Island before marching with the French and remaining soldiers of the Rhode Island Regiment on 18th June, and remained with the combined forces at Yorktown where he would have witnessed, and perhaps overseen the work of those formerly enslaved men of the Rhode Island Regiment; as they secured the American lines and batteries leading up to the battle.

The younger Rochambeau remained with his father through the winter encampment at Williamsburg, Virginia until the following spring.

Reportedly appointed to lead the expedition against the uprisings because of his intense hatred for blacks, Rochambeau waged a war of extermination against the rebellious enslaved workers. In March 1803, the ship Napoléon brought with the remainder of it’s cargo, one hundred Cuban dogs, a breed similar to one found on Santo Domingo, whose size was compared to the largest Russian greyhound, with a terrier like head. These were well known as man-hunting dogs, and to prove to point, Rochambeau set up a grisly display in one of the main market squares.

Starved for days before the event, Rochambeau had the enslaved servant of his chief-of staff paraded to the town arena, and tied to a pole. Teams of dogs were then released, and the enslaved man cut open to incite the beasts to tear him apart.[xvi]

Other stories tell of Rochambeau releasing slaves into nearby swamps so that the dogs could hunt them down for sport. The younger Rochambeau also hold the reprehensible distinction of operating the first “gas chamber” when he order sulfur dioxide to be thrown into the hold of a ship full of enslaved captives.

Christophe continued to fight under General Dessalines until the French retreated in late 1803 and the General declared independence from France in 1804.

In his retreat from the fall of Cap Francais, the brutal Rochambeau fled aboard the frigate Surveillante but was captured by a British squadron under command of Captain John Loring. He was brought to England where the Vicomte de Rochambeau lived as in exile, a prisoner on parole for nine years.[xvii]

Saint Domingue would be renamed the island of Haiti, the name the indigenous Taino people had called the island before Columbus’ arrival.

In the ensuing months, Dessaline and other leaders waged an extended war of revenge, herding the remaining white Frenchmen into captivity, or torturing and killing them outright.

Reportedly, Christophe used his influence t persuade the General to spare the lives of non-French whites in Cap Francais, as well as those Frenchmen who had treated blacks honestly, and those who served the community such as priests and surgeons.[xviii]

Dessalines then took on the role of Emperor, proclaiming himself Jean-Jacques the First, Emperor of Haiti. Over the next two years, he would solidify his role as sole ruler of the island. Haiti was still volatile, and unrest only grew under the new regime that shrugged off and attempt at separation of powers, and ignored the basic rights of individuals. An attempted invasion by the Emperor’s forces to quell rebellion on Danto Domingo failed miserably in 1805, and by the fall of the following year, he would die at the hands of his own troops, attempting to corral another uprising. His body was mutilated and dragged through the streets of Port-au-Prince.

Four months after the death of Dessalines, An election was held by the two factions of blacks and mulattoes that still contested control of the island. Henri Christophe was elected as leader of the “State of Haiti”, comprising the north and west, while Alexandre Pétion, the leader of the mulatto faction was named leader of the “Republic of Haiti” in the south. The two factions would rival each other for the next fourteen years.

Henri Christophe had always favored a complete break with France, even advocating a change to the English language in the wake of British architects, teachers, and protestant missionaries arriving on the island. The mulatto faction under Pétrion favored continued relations and material and cultural relations with France.

Despite their differences, as historian Wim Klooster points out, there were many similarities. Both regimes emulated European politics, banned the practice of voodoo, and supported organized religion. A new constitution of 1811 made his state a kingdom, and proclaimed Christophe as King Henry I. The constitution also allowed for the creation of a court society, similar to Versailles, with former slaves elevated to princes, dukes, counts, and chevaliers.[xix]

A democracy, as those Chasseurs had helped to fight for in North America was not to be. A statement written by the new ruler attempted to persuade the world why the revolution in Haiti had ended in monarchy.

“Although we are also a new people” the document stated, “our needs, morals, virtues, and vices are those of the people of Antiquity. We recognize therefore, with the great Montesquieu, the excellence of paternal, monarchial government.”[xx]

A plaque commemorating the sacrifice of the Fontange Legion was dedicated at the Cathedral of Saint Marc, Haiti by the United Sates Secretary of State Cordell Hull in 1944.

In 2007 a monument commemorating the contributions of the Chasseur-Volontaires de Saint Domingue was unveiled in Savannah, Georgia. At its unveiling, the monument was constructed of four bronze statues. Two additional sculptures were added in 2009 to complete the monument which depicts a group of five uniformed and armed soldiers with rifles at the ready. One soldier is seated and slumped with his hand to a chest wound. Beside the armed soldiers stands a young drummer boy, representing the twelve year old Henri Christophe.

A plaque on the base of the octagonal monument reads:

“The largest unit of soldiers of African descent who fought in the American Revolution was the brave “Les Chasseurs Volontaires de Saint Domingue” from Haiti. This regiment consisted of free men who volunteered for a campaign to capture Savannah from the British in 1779. Their sacrifice reminds us that men of African descent where also present on many other battlefields during the Revolution.” [xxi]

[i] Desmarais, Norman America’s First Ally: France in the Revolutionary War Casemate Publishers, 2019 p. 201

[ii] Klooster, Wim Revolutions in the Atlantic World: A Comparative History New York University Press 2009 p. 89

[iii] Ibid.

[iv] Desmarais, p. 201

[v] Ibid, p. 202

[vi] Ibid, p. 204

[vii] Ibid.

[viii] Ibid.

[ix] Leveque, Christine Black Cosmopolitans: Race, Religion and Republicanism in an Age of Revolution University of Virginia Press 2019 see https://open.upress.virginia.edu/read/black-cosmopolitans/section/b2fd2f1e-bfb2-48ae-9768-e25c602c58d8 accessed 8/11/2024

[x] Leveque, see https://open.upress.virginia.edu/read/black-cosmopolitans/section/b2fd2f1e-bfb2-48ae-9768-e25c602c58d8 accessed 8/11/2024

[x] See https://www.slaverymonuments.org/items/show/1169

[xi] Klooster, p. 87

[xii] Leveque, Christine, Black Cosmopolitans

[xiii] Ibid.

[xv] Rochambeau, Memoirs of the Marshall Count de Rochambeau Paris, 1838 p. 42

Disappointingly, Rochambeau’s memoirs mention nothing of the Col. Christopher Greene or the “black regiment”, by 1781 merged with the 2nd Rhode Island by the time of their departure from Newport and Providence.

[xvi] Girard, Phillipe R. War Unleashed: The Use of War Dogs During the Haitian War of Independence La Review Napoleonica, No. 15, 2012

[xvii] Mobley, Christina A War Within the War from Haiti: An Island Luminous Duke University, July 31, 2020 see http://islandluminous.fiu.edu/part02-slide11.html

[xviii] Klooster, p. 111

[xix] Ibid, p. 114

[xx] Ibid.

[xxi] See https://www.slaverymonuments.org/items/show/1169