by John B. Dower

As Caesar and Moses toiled on one of the Cocumscussoc Plantation farms in the late summer of 1776, word came from Philadelphia to Providence concerning the future of the colonies in America. The Second Continental Congress had convened earlier in Philadelphia, culminating with all thirteen colonies voting to officially part ways with Great Britain and announce their intentions in the Declaration of Independence. Such notions of autonomy were nothing new in Rhode Island. During the past few decades, the rising friction between England and its North American provinces, Rhode Island had found itself in the middle of the fray over self-determination and increasing taxation by the British. From the Gaspee Affair in 1772, where Rhode Island colonists burned a British patrol boat looking for smugglers, to the General Assembly, having that past May been the first of the thirteen colonies to vote to “end its allegiance” to the British crown,[1] the smallest colony had continued to stir the pot of dissent. Indeed, Caesar and Moses (who up to that point were probably only known by their given names) had heard all of the blusters of independence spread through the region in recent years. What, if anything, did any of this increasingly more ominous talk of insurrection mean to them? In just two short years, they would find out.

Caesar and Moses were two of several enslaved people that worked the plantation at Cocumscussoc in North Kingstown, Rhode Island. As it turned out, slavery would indeed be an issue for many during the fight for independence. Almost immediately after the first publication of the Declaration of Independence was released, the document's hypocrisy as it related to slavery was condemned throughout the colonies and in England as well. The virtuous second line of the Declaration of Independence had created a paradox- “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of happiness.” Squaring the words with the realities of slavery proved problematic in 1776, and as we now know, would for a very long time. For the time being, life went on at Cocumscussoc just as it had for over a century.

Cocumscussoc is the area on the west shore of the Narragansett Bay that was the summer home of the Narragansett people and, in the late 1630s, the site of trading posts of Roger Williams and Richard Smith. According to Roger Williams himself, Richard Smith “put up the first English house” in Narragansett country at Cocumscussoc.[2] What would later become the “great house” of the plantation was initially called Smith’s Castle (as the historic house on the site is known today) and served as a garrison house during the 17th century. The original house was burned in 1676 during King Philip’s War and then rebuilt in 1678 by Richard Smith Junior. When the younger Smith died childless in 1692 after predeceasing his wife, most of the estate went to his nephew and niece, Lodowick Updike and Abigail Newton Updike. Lodowick and Abigail, who just happened to be first cousins and wed to each other, would accelerate the growth of Cocumscussoc into a formidable plantation going into the eighteenth century. At its pinnacle, under the ownership of Lodowick’s son Daniel, Cocumscussoc encompassed some three thousand acres.[3] By the time of the Revolutionary War, the plantation had once again passed down in the Updike family to Daniel’s son, Lodowick, owner of Caesar and Moses. The farming operation on which Caesar and Moses worked was less impressive than it had been just decades earlier, as it now amounted to around eight hundred acres, with other areas leased out to tenant farmers. [4] However, even at this reduced capacity, Cocumscussoc still required several enslaved people to maintain its viability.

Narragansett country included those areas in what had been Kings County (known today as South County, but technically Washington County). During the middle of the eighteenth-century, the plantations in that region established a “social and economic organization” that was unique “in its dependence on slave labor for large-scale agriculture.”[5] The lack of a white labor force, an abundance of fertile lands, and the temptation of cheap labor made a dreadful combination that accelerated the number of Blacks enslaved throughout southern Rhode Island. Although the Narragansett region's slaveholders never came close to challenging the numbers of the most massive plantations seen in the southern colonies, the number of enslaved per household was higher than almost anywhere else in New England.[6] From 1700 to 1750, the number of slaves rose from 85 to 625 in Narragansett country,[7] which becomes more abhorrent when one realizes that many households in the region participated in the practice, and it was not just limited to the large agricultural enterprises.

However, the "great planters” of Narragansett were responsible for the preponderance of enslaved people living there, with many owning ten or more and some holding as many as forty.[8] While it was not until the Federal Census of 1790 when the enslaved were identified differently from free people of color, the Rhode Island Colony Census of 1774 can be beneficial in confirming what households in which towns contained blacks and Indians. Newport had the largest number of Blacks and Indians at the time of the census, 1292 out of a total population of 9208.[9] South Kingstown had 650 people of color out of 2835, and North Kingstown had 290 out of its 2472 inhabitants.[10] The percentages of people of color in the three towns were- North Kingstown 12%, Newport 14%, and South Kingstown, where most of the plantations flourished during the 1700s, 23%. The average in towns across the entire colony was just under 9%. All of the localities registered numbers well above what was the norm throughout most of New England. In one household in North Kingstown in 1774, Blacks made up precisely 50% of the occupants.

In the census taken for Rhode Island in 1774, Lodowick Updike's listing shows 22 members of the household, 11 Black and 11 white.[11] We cannot be sure that all eleven of the people of color were enslaved at that time, but the Updikes had a chronicled history of slavery for the previous eight decades. The first documentation of slavery at Cocumsuccoc dates back to the inventory taken after Richard Smith Junior’s death in 1692, which recorded his ownership of eight enslaved persons.[12] The probate inventory for Lodowick’s father, Daniel, in 1757 (which incidentally lists both Caesar and Moses) contained 19 enslaved individuals.

The will of Daniel Updike listing Moses and Caesar.

As we have seen, slavery was nothing new at Cocumsussoc on the eve of the American Revolution. It may have taken place in even larger numbers than what records indicate, “as it was popular to conceal numbers from the observation of the home government,”[13] especially during the turbulent times where taxation on all types of “property” was a lightning rod. Not surprisingly, the census ordered in 1774 was by the British Board of Trade's explicit request, increasing the likelihood that colonists did conceal their business practices, including their workforce size. Further indications of a larger slave population in and around Cocumscussoc can be found with documentation of an “extensive burial yard” for the “black servants” of the Updikes and two other families located just north of Smith’s Castle.[14] A minimum of eighty marked graves was identified, and it was believed many more existed. Pervasive slavery had clearly existed for some time at Cocumscussoc, even though the Updike plantation itself had diminished in size by the 1770s.

We know with a great deal of certainty that both Caesar and Moses had lived at Cocumscussoc before 1757, thanks to the probate inventory taken at Daniel Updike's death. We also know that Caesar was born sometime around 1755 and identified as "Mustee" (mixed race of Indian and Black ancestry).[15] Scant little information is available regarding Moses’ early life, including when he might have been born or if he was in any way related to Caesar. Early in the 1700s, Africans began to be brought directly into Narragansett country,[16] and by the middle of the century, the enslaved Black population in the region "increased naturally."[17] If Caesar was identified correctly as a mustee, he more than likely had ancestry tied to the Indigenous population in Rhode Island, as it is thought that indentured Indians had mixed with enslaved Africans at Cocumscussoc in years prior.[18] Unfortunately, more personal information on the two enslaved young men at Smith's Castle, before the American Revolution, has never revealed itself.

We can glean a considerable amount of general information about life on Narragansett plantations from a variety of sources, which are suggestive of the duties performed by Caesar and Moses. Cocumscussoc, like most of the other agricultural enterprises in the area that survived on enslaved labor, focused primarily on "dairying."[19] Caesar and Moses likely had some participation in dairy activities, although that was probably not their only responsibility. Enslaved people on farms "would have performed myriad tasks and worked a variety of jobs"[20] throughout their long workday. Other duties, in addition to tending dairy cattle and helping produce butter and cheese, would have included- carrying water, cutting and carrying firewood, planting and cultivating some crops, and fence building and repair. The list is probably endless as the “jack of all trades” was nearly “indispensable to Yankee masters.”[21] Nevertheless, for all their value as workers, it was likely Caesar and Moses slept their nights away in an outbuilding or barn, as only the house servants generally occupied sleeping quarters in the main house on most plantations in New England unless it was bitter cold.

The mundane life working on a farm in eighteenth-century Rhode Island was insufferable for the enslaved. Some lucky individuals could buy their freedom by working other jobs once their everyday tasks were completed on the plantations. It was also common for masters, upon their death, to reward their enslaved with freedom if they had served their owners well.[22] Richard Smith Jr. intended to do that with some of the enslaved he owned, but there is no proof that it ever took place. The other method was also used by the enslaved to achieve freedom, running away from their masters. No record of Caesar or Moses having ever attempted to flee Cocumscussoc seems to exist, although others at the Updike farms had tried. Freedom must have still seemed out of reach in 1778 for Caesar and Moses.

In the two years following the Declaration of Independence, life dragged on for the enslaved in Rhode Island, and rhetoric of liberty swirled all around them as the War for Independence intensified. Before the American Revolution, Blacks had "served in every war of consequence" during the colonial era.[23] The rolls of militias regularly contained the names of men with Indian and African ancestry, but the role of both free Blacks and free Native Americans, as well as the enslaved, became a matter of contention as the war progressed. Before American leaders had fully addressed men of color's participation in the rebellion, many free blacks and Native Americans had already aligned themselves with the colonists seeking independence from England. Many more had chosen to take up with the British.

While men of color did participate on the American side in the early months of the war, “a pattern of exclusion had developed” as time went by.[24] When George Washington took command of the Continental Army, he banned Blacks' enlistment but eventually allowed those already fighting for the American cause to continue their service. However, the insurrection leaders had still found themselves in a predicament over their Declaration of Independence and how to harmonize the document with slavery. Even in Kings County, philosophical differences persisted whether to use men of color, both free and enslaved, to fight for the American cause. For the Narragansett planters, it was purely a matter of economics and not wanting to relinquish their free labor source. Shortly, it would be neither a philosophical concern nor a matter of economics that would change some enslaved Rhode Islanders' lives and allow their participation in the Continental Army.

The Revolutionary War dragged on in 1778, with the Americans having little to show in the way of optimism beyond a surprise victory at Saratoga the year before. It had been a brutal winter in 1777-1778, especially for the Rhode Island troops that remained at Valley Forge, and the contingent from the smallest state was at that point “greatly undermanned.”[25] Not surprisingly, General Washington was already in communication with Rhode Island leaders General James Mitchell Varnum and Governor Nicholas Cooke on addressing the problem of filling their state quota. After some back and forth, Varnum halfheartedly suggested a plan allowing enslaved men of color to enlist into the Continental Army. Already in an ever more difficult position concerning on-going slavery in America, Washington’s situation had become worse with Dunmore’s Proclamation in 1775, which lured many of the enslaved in Virginia to join the British ranks with the reward of freedom. Washington eventually gave Varnum’s plan his indifferent approval.

On February 14th of 1778, the General Assembly of Rhode Island also gave their blessing to Varnum's scheme to enlist enslaved Black men from within the state. Although the act was several paragraphs long, this one excerpt summarizes the significance of the measure as it related to the enslaved- "…upon passing muster…be immediately discharged from the Service of his Master or Mistress…”[26] While there had been "no great enthusiasm for the rebellion in Narragansett country," eventually, most of the plantation families had “aligned with the patriot side.”[27] When the act passed, a provision was put in place that stated- "…Compensation ought be made to the owners…”[28] Still, many of the Narragansett planters were unhappy over the prospect of losing their enslaved workers, mainly because the they could enlist under their own volition. Upwards of a hundred did enlist.

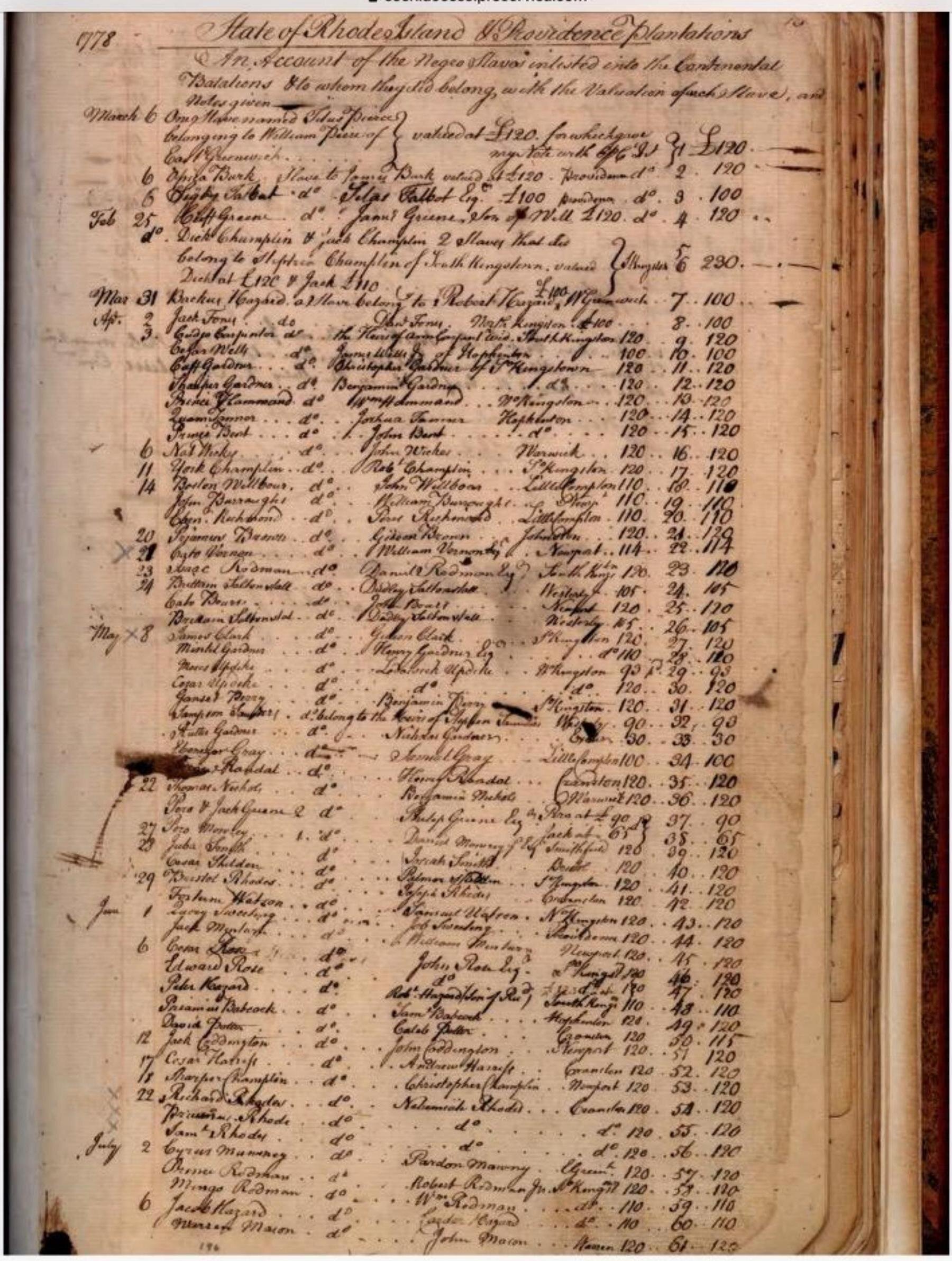

The reaction to the new act by Lodowick Updike is unknown, but we know that by March of 1778, Moses and Caesar became two of the enslaved Black men from Rhode Island that enlisted in the Continental Army in exchange for their freedom.[29] Much information can be garnered from the “General Treasurer’s Account,” the list used by the state to compensate the owners of the enslaved that had enlisted, and other treasurer’s records and general assembly records. Between February 15th and June 10th, some 100 plus men enlisted, most of whom had worked at Kings County's prominent plantations. Lodowick Updike was compensated £120 for the loss of Caesar's service, which was the maximum allowed. However, the plantation owner received a reduced rate of £93 for Moses, an indication that the enslaved man may have been older or had some physical limitations. It is believed that the total number of enslaved mustees, mulattoes, Indians and Blacks that eventually joined the “outfit” was around 125.[30] This number increased when free men of color that had previously joined the army were added to the 1st Rhode Island Regiment that summer. Caesar and Moses were now Updikes, and they were off to war with those other men of color from the nearby farms.

General Treasurer’s Accounting List on which Moses and Caesar appear.

The unit raised by the 1778 legislation, and that Moses and Caesar became members was known by many as the "Black Regiment." James Mitchell Varnum's extraordinary plan was not to only incorporate some formerly enslaved men into some regiments of the Rhode Island contingent but rather raise an entire regiment of Black soldiers.[31] It was expected that some 300 enslaved men of Rhode Island would enlist, but that notion was destined to fail. Under increased pressure from slave owners, the General Assembly reversed the enlistment legislation after a few months and effectively ended nearly all enlistments of enslaved. Even though most of its companies were made up almost entirely of men of color at the reformation of the 1st Rhode Island Regiment in the summer of 1778, and after a series of reorganizations coupled with the losses of men of color being replaced by white soldiers, the regiment became increasingly white over time. None the less, when the call to action came to the 1st Rhode Island in their very own state later that first summer, it was segregated and made up entirely of formerly enslaved Blacks led by white officers.

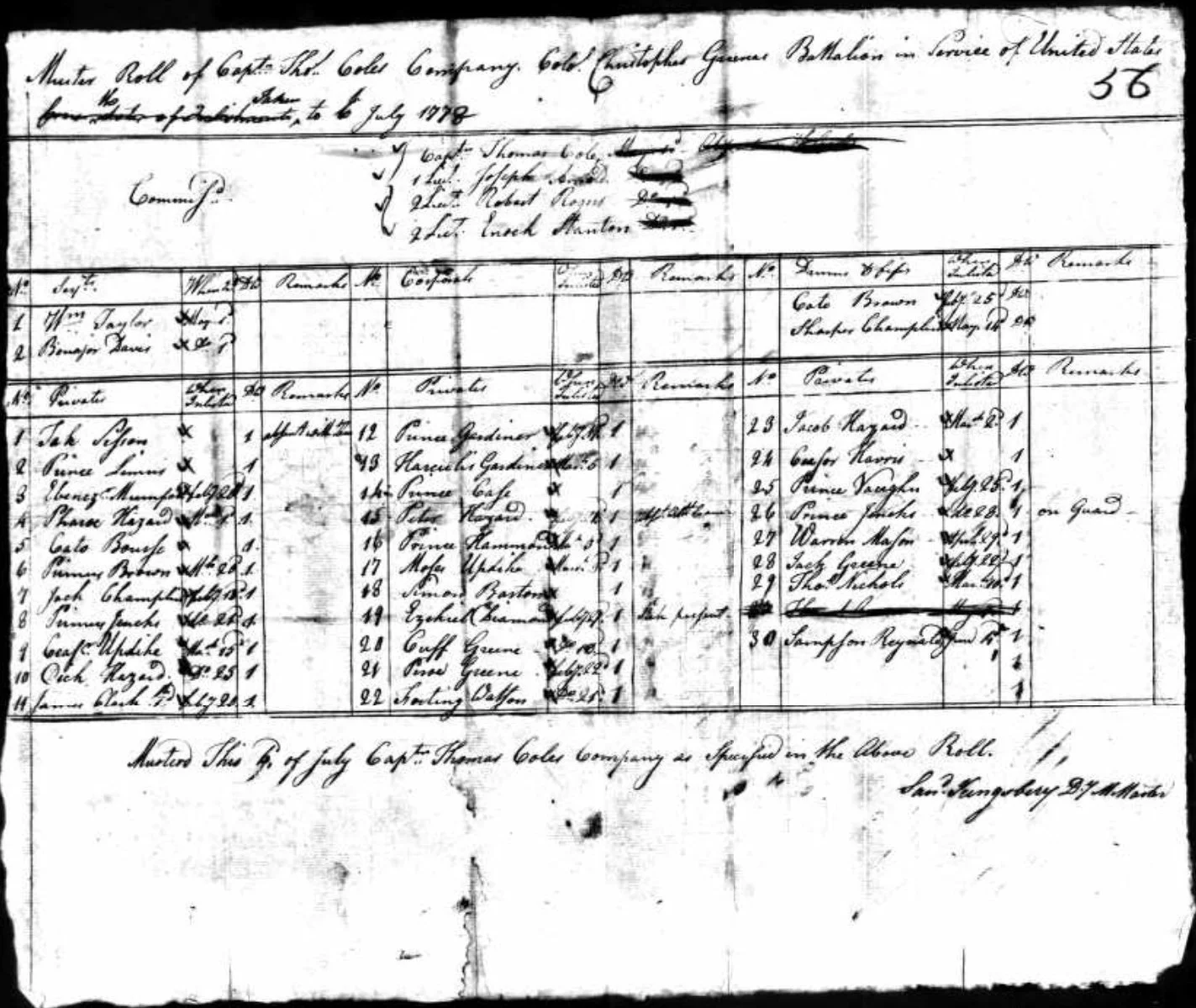

After “learning the manual of arms” in the first weeks after enlisting,[32] Moses, Caesar, and their compatriots soon found themselves heading to Aquidneck Island, where Newport was located. At the time, the British still occupied Newport but had pulled back troops at the island's northern end. With the impending arrival of the allied French fleet to the south, American officials decided it was time to take back Newport by siege from the north in August of 1778. Unfortunately, an early departure by the French fleet and other factors led to the patriot's being forced to retreat off Aquidneck Island. By the end of August several engagements took place with the British and loyalist forces as the American troops retreated. Caesar appears on muster roles before and after what is known as the Battle of Rhode Island, and the 1st Rhode Island Regiment was pressed into action that day, so we can assume Caesar was present. Moses is listed as “Sick Absent” on the muster just prior to the Battle of Rhode Island, so his participation is in doubt. Several other soldiers suffered from disease at the time, including some that perished. As the retreating American troops were being pursued by the British, the Redcoats were “met by firmness” from the 1st Rhode Island.[33] Caesar and Moses's role on that day will more than likely never be known, but it should suffice to say they answered the call to defend their country.

The first muster roll of Moses and Caesar from July of 1778.

Several months after the Battle of Rhode Island, the 1st Rhode Island Regiment was at their winter quarters in Warren, Rhode Island. That will be the last we hear of Moses Updike as the muster roll for December lists him as deceased on December 20, 1778. Whether Moses eventually perished from disease as did thousands of others in the Continental Army will remain a mystery.

Caesar spent the next few years in anonymity other than appearing regularly on the muster rolls. His regiment was attacked at Pines Bridge in New York, where several soldiers, including officers, were killed, but Caesar, like most soldiers who participated in the American Revolution, remains unnamed in accounts of the fighting. At the Siege of Yorktown in 1781, it appears that Caesar's company was not involved directly at the frontlines, which was true of the vast majority of the soldiers present for the decisive victory. A march to Oswego, New York, that ended without any fighting would be the last event of Caesar’s five-year military stint. He was furloughed at Saratoga along with many of the formerly enslaved men from Rhode Island on June 15, 1783 and later honorably discharged.

Moses and Caesar Updike were relatively obscure figures like most men who fought for the American cause. The story of the two Updikes was fairly typical of the enslaved that chose to fight to gain their individual freedom while serving the fledgling nation. Many died, while some served for five years and were honorably discharged. Yet, an analysis using the list of enslaved men that enlisted from “General Treasurer’s Accounts,” along with individual entries of payments made to additional slaveholders by the treasurer[34], payments ordered by the general assembly to owners of enlisted slaves[35], the military records and compilations found in the Regimental Book for Rhode Island[36] and Forgotten Patriots,[37] tell us that Moses and Caesar, and the men that enlisted with them, were anything but typical. Of the approximately 125 former slaves from Rhode Island, 51 died of unknown causes (most likely disease) during the five years from 1778 to 1783, at least 11 were killed in action, 3 of the several POWs were never seen again, 3 never mustered in after signing up, 8 deserted permanently (a number well below the Continental Army average), and 42 were honorably discharged. Many suffered from starvation, injuries and illnesses that were never documented.

The Declaration of Independence inspired “the notion that enslaved people had their natural liberty stolen.”[38] The Updikes saw it that way, and their enlistment is the confirmation. They served virtuously for America in the process of getting back that freedom. Caesar was awarded an Honorary Badge of Distinction for giving five years of his life to the cause. Moses gave his life. Only Caesar was rewarded with something that both Updikes believed was worth dying to achieve.

Notes:

[1] Christian McBurney, The Rhode Island Campaign: The First French and American Operation in the Revolutionary War (Yardley, Pennsylvania: Westholme Publishing, 2011), 10.

[2] Howard Millar Chapin, The Trading Post of Roger Williams with those of John Wilcox and Richard Smith(Providence: E.L. Freeman Company, 1933), 16.

[3] Wilkins Updike, History of the Episcopal Church in Narragansett Rhode Island (New York: Henry M. Onderdunk, 1847), 180.

[4] Carl R. Woodward, Plantation in Yankeeland (Chester, Connecticut: The Pequot Press, 1971), 63.

[5] Joanne Pope Melish, Disowning Slavery: Gradual Emancipation and “Race” in New England 1780-1860 (Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press, 1998), 13.

[6] Lorenzo J. Green, The Negro in Colonial New England (New York: Columbia University Press, 1942), 98.

[7] Woodward, 72.

[8] Jared Ross Hardesty, Black Lives, Native Lands, White Worlds: A History of Slavery in New England (Boston: University of Massachusetts Press, 2019), 91.

[9] General Assembly of Rhode Island, Census of the Inhabitants of the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations in 1774 (Providence: Knowles, Anthony & Company, 1858), 239.

[10] Ibid., 239.

[11] Ibid., 83.

[12] Woodward, 53.

[13] Updike, 174.

[14] Rhode Island Historical Cemetery Commission, “Cemetery Database,” cemetery number 246, accessed January 3, 2021, rihistoriccememteries.org/newsearchcemeterydetail.aspx?ceme-no=NK346

[15] Bruce C. MacGunnigle, Regimental Book for Rhode Island 1781 &c. (East Greenwich, Rhode Island: Rhode Island Society of the Sons of the American Revolution, 2011), 37.

[16] Christy Clark-Pujara, Dark Work: The History of Slavery in Rhode Island (New York: New York University Press, 2016), 27.

[17] Ibid., 51.

[18] G. Timothy Cranston and Neil Dunay, We Were Here Too: Selected Stories of Black History in North Kingstown(Create Space Independent Publishing, 2015), 85.

[19] Greene, 105.

[20] Hardesty, 86.

[21] Greene, 119.

[22] Woodward, 73.

[23] W.B. Hartgrove, “The Negro Soldier in the American Revolution,” The Journal of Negro History 1, no. 2 (1916): 112.

[24] Benjamin Quarles, The Negro in the American Revolution (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1961), 13.

[25] Ibid., 55.

[26] Rhode Island State Archives, “Act creating the 1st Rhode Island Regiment, also known as the "Black Regiment," 1778," accessed January 19, 2021, https://www.sos.ri.gov/assets/downloads/documents/Black-Regiment.pdf

[27] Woodward, 133.

[28] Rhode Island State Archives, “Act creating…”

[29] Rhode Island State Archives, “General Treasurer’s Accounts 1761-1781,” accessed January 9, 2021, https://sosri.access.preservica.com/uncategorized/IO_69917081-a9d3-4b27-bfb6-9b45994e00ad/

[30] McBurney, 47.

[31] Robert A. Geake and Loren Spears, From Slaves to Soldiers: The 1st Rhode Island Regiment in the American Revolution (Yardley, Pennsylvania: Westholme Publishing, 2016), 20.

[32] Quarles, 77.

[33] McBurney, 187.

[34] Rhode Island State Archives, “General Treasurer’s…”

[35] Rhode Island and John Russell Bartlett. Records of the colony of Rhode Island and Providence plantations, in New England: Printed by order of the General Assembly. Providence: A.C. Greene and brothers, state printers [etc.], v8-10.

[36] MacGunnigle, 59-79.

[37] Eric G. Grunset, Forgotten Patriots: African American and American Indian Patriots in the Revolutionary War(Washington, D.C.: National Society Daughters of the American Revolution, 2008), 187-252.

[38] Hardesty, 128.