By Robert A. Geake

Of the many friendships formed during the glorious cause of the American Revolution, few would, on the surface, seem as improbable as that of the late émigré to America and starry-eyed enlightened political philosopher Thomas Paine and the pragmatic, reserved, and ardent military strategist General Nathanael Greene.

Their backgrounds were not only miles apart in distance but upbringing as well. Paine grew up in a thatch-roofed house in a section of Norfolk, England, known as the Wilderness[i], while Greene was raised in the fine colonial Georgian manor built from the well-rooted Rhode Island family’s shipping business.

But the bonds they shared as adults, their passion for American liberty and self-rule, and the morals instilled in them by a Quaker upbringing would remain the strongest threads in the tapestry that events would weave of each life:

a commonality in working for the greater good, and to give all Americans, including those of color, the rights of life and liberty; and the opportunity to pursue their own happiness.

Thomas Paine had been baptized an Anglican and remained on the church of England's records as such until he departed for America. As a boy, however, he dutifully attended Quaker meetings with his father, Joseph. A keen-eyed, intelligent son of an artisan staymaker, the pious eight-year-old Paine would pen his first literary achievement when he wrote an epitaph for his deceased pet:

“Here lies the body of John Crow

Who once was high, but now is low

Ye brother crows take warning all

For as you rise, so you must fall”.

Despite an early penchant for science, Paine's parents' means could support only a limited education, and he received no formal education beyond the age of twelve. As a result, his learning from then on came by his own accord, and through benevolent sponsors, he would acquire as he reached adulthood.

Nathanael Greene, though born in far better circumstances, was raised to be humble, as the Quaker beliefs mandated both in spirit and in dress; and it was to this life that he and his brothers were tethered at the farm of the elder Nathanael Greene. It was a hard life, even for strong, active young men, and among the chores given to the boys through the seasons on the farm, it is plausible that at the age that Paine was mourning his pet, his later friend and brothers were shooting crows above the fields of Potowamut.

As Nathanael Greene grew into young adulthood, his passion for reading and learning increased, and he sought friends outside the Quaker community to aid in his education. One such benefactor was Newport minister Ezra Stiles of the Second Congregationalist Church. Among the ministries the pastor provided were preaching to smaller congregations in Tiverton and Little Compton; and, as early as 1771, held separate Bible meetings for members of the black community, as he recorded on February 24, 1772

“In the Evening a very full and serious Meeting of Negroes at my House, perhaps 80 or 90: I discoursed to them on Luke XIV 16, 17, 18, …They sang well. They appeared attentive and much affected; and after I had done, many of them came up to me and thanked me, as they said, for taking so much Care of their souls.”[ii]

The minister encouraged the young Greene and not only advised him spiritually but also introduced him to William Gill and Lindley Murray, both studying law at Yale University. With the help of these friends, and later, David Howell of Rhode Island College, Greene was able to borrow books and study at will and learn the social graces from these more worldly young men that would enable him to become a gentleman.[iii]

Greene settled into managing some of the family's affairs, and a house was built for him in Coventry, Rhode Island, above the Pawtuxet River and the family forge he managed. His reputation in the community continued to grow, and in 1770 he was elected to represent the town in the General Assembly. T was during this term of service that events would propel him into the revolutionary upheaval to come.

In the wake of the infamous Gaspe incident, in which a British revenue schooner ran aground and was burned by Providence and Warwick insurgents caused Greene, to seek military training and learn tactical defense from the available books he could find. He began to drill with the Plainfield, Connecticut militia, and in 1773 was called before the elders of his Meetinghouse and expelled from meetings for his participation in military exercises. The following year, he signed a pact with attorney James Mitchell Varnum to form a militia group and petitioned the state to be incorporated as the "Kentish Guard."

As Thomas Paine reached adulthood, his status as an unskilled laborer gave him little choice but to become an apprentice in his Father’s business. He would not break free of these constraints until an opportunity came for him to practice the same craft in London, and then, on January 17, 1757, he signed aboard the British privateer King of Prussia.

This seemingly impulsive act of independence had occurred once before, but his Father had tracked him down soon enough to dissuade him from signing aboard a vessel that was literally shot to pieces the moment she left the channel. This time, it proved to be an act of good fortune, Paine suddenly being part of a crew that captured eight enemy vessels and their treasure in as many months; returning to the London docks in late summer.

It was then that the city itself, with its bookstores and coffeeshops and free lectures, fed again Paine's appetite for learning and increasingly for discourse; with friends he made in the coffeeshops and with printers who would ultimately produce his first pamphlets in defense of workers rights that brought him his first recognition, but it was little comfort for the failure of his own business, and of an impulsive marriage that ended unhappily in the spring of 1774.

Having sold all his goods, he returned to London and made his way to 36 Craven St. to meet with the Ambassador from North America, Benjamin Franklin. It was an act of uncanny nerve and confidence that Paine would sit down with and obtain a letter of recommendation from one of few celebrities from the colonies that could assist someone like Paine, unlikely as it was that Franklin had heard of the aspiring author.

Paine's biographer, Craig Nelson, assigns their immediate friendship to their common origins of being born

“near the bottom rungs of Anglo-American society. Both had acquired an advanced education by their own efforts, and both believed in cultivating an elegant and stylish simplicity as an outward manifestation of republican ideals.”[iv]

But Paine had something more that Franklin and others, including Washington, and Nathanael Greene, would see: an absolute and sincere belief in the cause of America and of democracy itself for mankind. In the years ahead, the country and lovers of liberty around the world would briefly elevate Thomas Paine to the level of the world’s greatest thinkers. But as he left Franklin’s doorstep, he had but more than a letter of recommendation and his boat ticket to America.

Three months later, after an arduous voyage, Paine was literally carried in a litter ashore at the port of Philadelphia. Sickness had plagued the hold, filled with servants and low-wage workers who could scarcely afford the ticket and the risk of the voyage. The thirty-seven-year-old Paine had been taken with a debilitating illness, quite removed from the rest of the ship. The letter he bore from Franklin saved him, for the lone doctor on the vessel not only saved many of the passengers and crew who had fallen ill but had Thomas Paine taken to his own house and nursed him some six weeks before he was well enough to find his own rooms and his own place in the Revolution that was to come.

Nathanael Greene had suffered setbacks as well. While he was among the founders of the new militia for Kent County, a childhood injury that left him with a slight but permanent limp in his gait now prevented him from being elected commander of the Kentish Guard. It must have been a crushing blow to the young leader, who had already spent many hours studying military history and drilling tactics so that the regiment would be disciplined and ordered when the conflict came, for by 1774; communities along the shoreline of Rhode Island were stoking the fires of freedom.

Greene nearly resigned, but Varnum persuaded him to continue as a private in the regiment.

He would dutifully march as a private with the Guard when they mustered after hearing news of the fighting in Lexington and Concord and, once assembled, marched for Massachusetts at dawn on April 20, 1775. The regiment was resplendent in new uniforms of red, green, and white; attracting a large crowd of cheering onlookers as they paraded along what is now North Main Street.

When they reached the state line in Pawtucket, a messenger overtook them with a demand from the governor that they not cross into Massachusetts. This order occasioned most of the men to lay down their arms, but Greene and his brothers, as well as another individual, procured horses and continued on, turning back only when they learned that the British had retreated to well-fortified Boston.

Soon after his return, Greene learned that he had been chosen to lead as general of the state’s army. Certainly, Greene, as a representative, had political friends, indeed, since the election of his brother Jacob as a deputy in the legislature, he had family as well. But as his biographer Gerald Carbone points out; what made Greene stand out more than these were his capabilities.[v]

The man who had been a private but days before now found himself in command of the thousand-strong Rhode Island Army of Observation. Most of the men, like Greene himself, had enlisted from inland farms or the wharves of seaside communities; there were some freeing themselves from apprenticeships, and others signing like Paine had done nearly twenty years before; for the adventure and possible fortune with the spoils of war. At best, some had six months of muster and drill training twice a week. None had so much as taken part in a skirmish, let alone faced an enemy in battle.

Greene tirelessly recruited from Rhode Island and installed a rigorous discipline in the Roxbury camp: no cards, no liquor, and show for muster clean and shaven. The discipline of the Rhode Island brigade compared with bedraggled units from other New England states was noticed by Washington as he reviewed the troops that would become the Continental Army.

His diligence was rewarded when Greene received a commission as a Brigadier General in the Army. At thirty-two, he became the youngest General in the Continental Army.[vi]

In July 1775, The Rhode Island brigade was encamped upon Prospect Hill, a half mile from British-held Charlestown. While there, Greene and the Rhode Islanders came under the command of Major Charles Lee, a singularly odd man to wear an American Officer's uniform. Lee had climbed to the rank of Major in the British Army, partly through his fighting in America during the French and Indian War, but he resigned his commission to become a soldier of fortune in the Russo-Turkish conflict of 1768-1774; a war which his Polish allies did not win, but which nonetheless earned him the rank of Major General.

The Siege of Boston, as it would be named, was a long, arduous summer of suffering heat and illness. Encampments on both sides were thinned out by dysentery and other "camp illnesses." At the height of the suffering, the British forces were losing thirty men a week to illness.

At the end of summer, Greene dispatched five hundred of the Rhode Islanders who were still fit for duty to assist the New Hampshire Regulars in fortifying the works at Ploughed Hill, a redoubt overlooking the Mystic River. Among these volunteers was Agustus Mumford, a friend of Greene's who had just recently raised funds for the poor and displaced residents of the city of Boston. Unfortunately, he became the first Rhode Island casualty of the Revolution when he ill-advisedly peered over the barricades and had his head taken off by a British cannonball.

As the Fall and then Winter approached, Greene could see morale sinking further among the recruits. He had feared all along that such inaction over these months could very well mean the dissolution of the American army. Washington, Greene, and others had at first favored a night-time raid guided by Glover's Mariner brigade of boatmen and landing across the Charles River before dawn. Instead, Washington dispatched Henry Knox and a convoy of oxen and horses to retrieve canon that American forces had captured months before at Fort Ticonderoga.

As weeks of inactivity passed, an expedition to Canada gained more favor among officers, and the original plan was abandoned as junior officers and troops were enlisted for the ill-fated march to Quebec. The Rhode Island brigade would part with some of their most able officers in Christopher Greene, a distant cousin of Nathanael, as well as Simeon Thayer and Samuel Ward. Greene occupied his men in building barracks on Prospect and Winter Hills for the bitter months that lay ahead.

That winter, Greene would write of the hardships they faced:

"We have suffered prodigiously for want of wood. Many regiments have been obliged to eat their provisions raw for want of fuel to cook it, and not withstanding we have burnt up all the fences and cut down trees for a mile around our camp, our sufferings have been inconceivable. The barracks have been greatly delayed for want of stuff. Many of our troops are yet in tents, and will be for some time, especially the officers. The fatigues of the campaign, the suffering for want of food and clothing, have made a multitude of soldiers heartily sick of service.”[vii]

By mid-December, the Continental Army was reduced to 5,000 troops, with many more eligible for release on New Year's eve. Greene and others had hoped that a bounty could be offered to men for recruitment, a sticking point for Washington, who opposed such an offer, even as he requested the means to raise an army of 20,000 from Congress.

Some re-enlisted as they realized a bounty was not to be. Others were reportedly shamed on their return home for leaving their brethren in arms to face the British in diminished numbers.

Nathanael Greene would write that during the Connecticut troop's exodus

“The people upon the roads expressed so much abhorrence at their conduct for quitting the Army, that it was with difficulty they got provisions.[viii]

Prospects grew dimmer in January when it was reported that half the men coming into camp could not be provided with a musket. Powder was also in short supply, and while guns had been promised from Philadelphia and other sources, the troops were left to hunker down and hope the British remained in hibernation. News of the failed expedition in Canada, as well as the death of General Montgomery and the capture of so many men and officers, must have brought morale to as low an ebb as imaginable.

Still, plans were underway to route the British from the city. With Cambridge Bay rapidly freezing over, Washington eyed a raid across the ice on the British works on Boston Neck. Though a good number of officers were hesitant to support such an action, Greene supported Washington's plan. However, a bout of jaundice would leave him bedridden for weeks and take away any opportunity to lead his men and retake Boston.

During these weeks, Colonel Henry Knox and his men returned with an arsenal of artillery. Now, the plan was to fortify Dorchester Heights and leave the British fleet in a vulnerable position. In the coming weeks, men would work furiously preparing fascines and the framing for gabines; one being a fencing constructed from bundled sharpened sticks, the other being wooden frames filled with dirt to act as barriers. Finally, on the night of March 4th, the anniversary of the Boston Massacre, some 1200 troops with entrenching tools and 300 ox carts were covered by 800 riflemen on the march to Dorchester, where they constructed the fortifications in a single night.

Though planning to retreat from the city had been underway, British General Howe was loathed to allow even the appearance that he was somehow forced to flee Boston to be his legacy to the American public and, even more likely, the press. It was surely with these thoughts in mind that he announced preparations for a 3,500 man assault on Dorchester Heights before the Americans were allowed to strengthen the fortifications.

The British rank and file persuaded him to change his mind in a council of war that evening. In those same hours, a great storm blew in from the south, the winds blowing out windows and driving vessels ashore.

By the 13th, the Americans had fortified Nooks Hill opposite the Heights and were raining a cannonade of shot at the British vessels in the harbor. The aggressive action of the Americans had its desired effect. On the morning of March 17th, the British garrison of 9,000 men, as well as just over a thousand loyalists, were safely ferried to eighty British transport vessels. Washington had pledged not to fire upon the British as they departed and ended the eleven-month siege of the city. The following day Brigadier-General Nathanael Greene was given charge of the city and the windfall of British cannon, horses, blankets, medicines, and other supplies that would aid Boston in its recovery. A month later, Greene was appointed Commander on Long Island, a key defensive position for New York.

Once again, Greene would lose his chance to show his military skills; another illness on the eve of battle left him unable to take part in the disastrous defeat the Americans suffered on Long Island. Had he been in battle, he would likely have been captured, as were many of the Rhode Islanders, and faced imprisonment until arrangements could be made for his release, much like his distant cousin Christopher Greene had undergone after capture at Quebec. It must have been a bitter disappointment once again, but in the coming months, Greene would have his baptism under fire.

Thomas Paine did not have to walk far from his newly acquired room in a riverside boarding house to find that the enlightenment ideals of the wealthy Newtonians he had left behind in London were also here, in somewhat humbler form among the craftsmen and mechanics in North America; one of whom ran a bookstore and printing press right next door. Moreover, the man whose friendship would launch Paine’s career as an author was Scottish-born Robert Aitken, a new emigrant as well, having arrived but three years before.

At the time of their meeting, Aitken’s was set to publish a new monthly magazine which would be called Pennsylvania Magazine, or American Monthly Museum. His conversations with Paine in the weeks that followed led him to offer the job of executive editor to the aspiring author.[ix]

It turned out to be a wise decision for the publisher. Within a few months, the readership had exceeded more than fifteen hundred paid subscribers.

Each issue was a cornucopia of essays on classical authors, the texts of letters between authorities and the crown, reports, descriptions of new scientific inventions, and treatises on self-improvement, among other varied topics. The issues were mostly written by Paine, lawyer Francis Hopkinson who taught, along with president John Witherspoon of the College of New Jersey. Each wrote multiple articles under pseudonyms such as Aesop, Atlanticus, Humanus, Justice & Humanity, and Vox Populi, a device used to persuade readers of many contributors as well as to mask the authors of the more incendiary articles.

Paine used his position to foster the “common good” as his biographer notes,

"as an editor, he regularly sought to publish articles on more substantive issues."

These included essays on the tragedy of the ongoing tradition of dueling, an essay on women's rights, and most notably, on April 14, 1775, when he published an essay entitled African Slavery in America, part of which read

“Our traders in men (an unnatural commodity) must know the wickedness of the slave trade, if they attend to reasoning, or the dictates of their own hearts…”[x]

This essay by Paine and the response it received have been cited as the cause of the organizing of the first abolitionist society in the world. It also earned him the friendship of another Philadelphian, Dr. Benjamin Rush. Any further effect, however, would soon be overshadowed by events that occurred just a few days later.

The events of April 18th in Concord and Lexington reverberated through the colonies. Militia mustered and marched to Cambridge or outlying communities in the weeks that followed. Less than a month after the skirmishes, the Continental Congress met in Paine's newly adopted city. As he followed events and the discourse that was undertaken in the Pennsylvania State House, his articles seemed written to stoke the fires of independence and threatened his job as his publisher feared the consequences.

Paine had no such compulsion to cease writing nor to use his pen to urge American independence, even if it were to come to violent means. Although raised as a Quaker, he had decided as an adult, as with Greene, who might have himself also declared

“I am thus far a Quaker, that I would gladly agree with all the world to lay aside the use of arms, and settle matters by negotiation; but unless the whole will, the matter ends, and I can take up my musket and thank heaven he has put it in my power.”[xi]

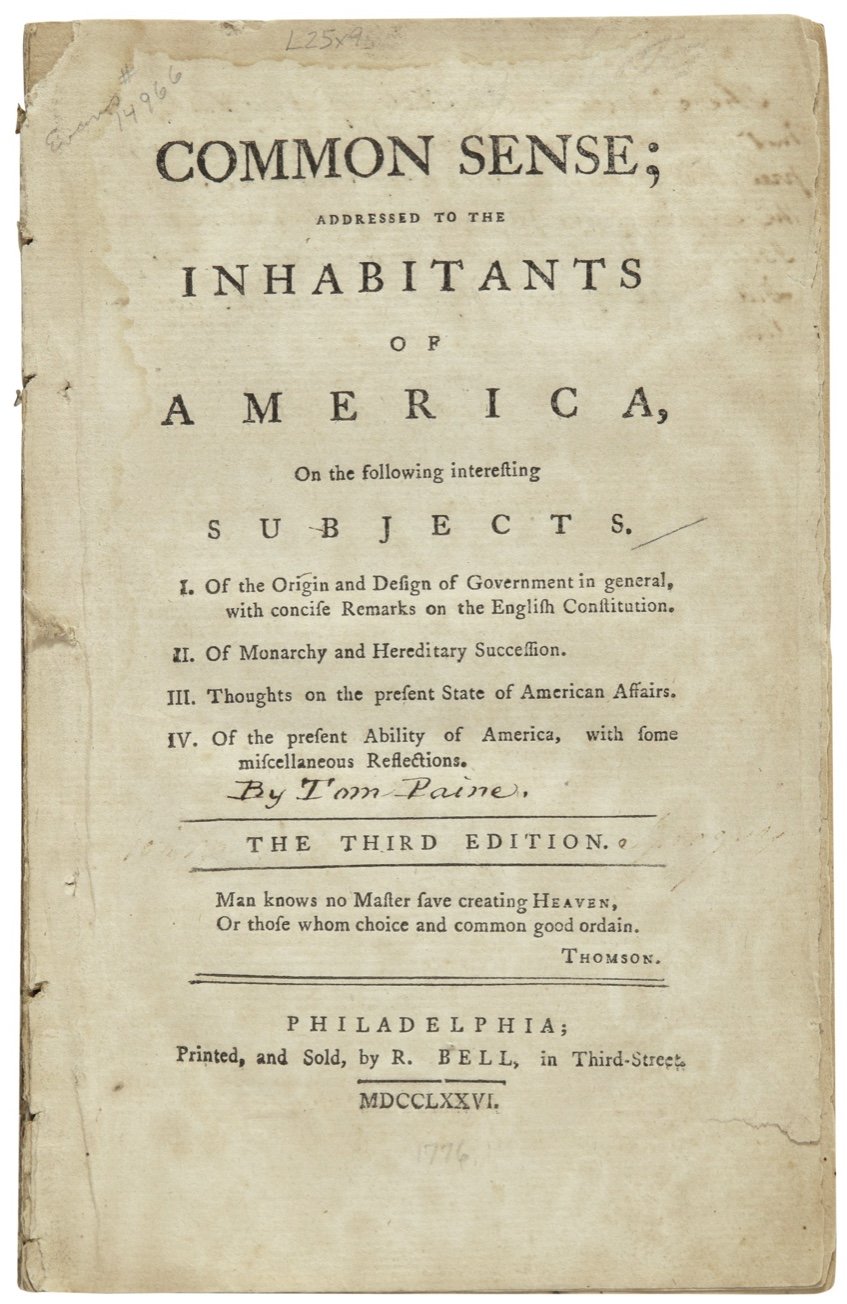

In the coming months, he would continue his critique of Great Britain's history of Empire, and in the Fall of that year, he began composing the first pages of what would be published as the pamphlet Common Sense, in which Paine systematically exposed, through the narrative of disastrous wars and misrule; the cracked pillars of sovereign rule, hereditary entitlement, and class divide which held up the Parthenon like façade of the late 18th century British Empire.

Paine proposed a solution between the countries, but it was nonetheless a solution that required liberty for America…

“…let a Continental Conference be held, in the following manner, and for the following purpose…to frame a Continental Charter, or Charter of the United Colonies;…fixing the number and manner of choosing members of Congress, members of Assembly, with their date of sitting, and drawing the line of business and jurisdiction between them: always remembering, that our strength is continental, not provincial; Securing freedom and property to all men, and above all things the free exercise of religion, according to the dictates of conscience; which other such matter as is necessary for a charter to contain”.

Historian Gordon Wood has rightly called Common Sense “ a remarkable document,…” and explains

“Few Americans had ever read in print what Paine said about Kings and George III, that “brute of Britain” who “made havoc of mankind.”[xii]

The pamphlet had its critics among Americans, most notably John Adams, who felt that the form of democratic government Paine advocated, and which, in fact, would strongly influence Pennsylvania's government and constitution, was

“So Democratical, without any restraint, or even attempt at Equilibrium, or Counterpoise, that it must produce confusion at every evil work."

I believe Adams's alarm at the responsibilities given to the common man, as the more lenient political writers phrased the hordes of poor and hardscrabble citizens who would be needed to uphold a republic, would quickly unravel what order and function had been in place.

But rather than some utopian ideal as many of Paine’s and the enlightenment influences had pronounced, Thomas Paine firmly laid out his plan for a new government that needed a constitution rather than a monarchy-the framers of such must be fixed upon… the true points of happiness and freedom.

"[To] those," Thomas Paine wrote, "unenlightened conservatives who dare to ask, "Where is the King?" Tell them, in America, THE LAW IS KING."

Common Sense would be printed legally through two dozen editions and sell 150,000 copies when most pamphlets printed at the time sold at best a few thousand copies. It was a pamphlet written for the common readers, devoid of the florid or magisterial prose of the pundits and ministers who were popular authors. As its title implies, the pamphlet strove to render simple common sense in its argument for separation from the crown, and embedded within, were lines that would become a stirring call to democracy:

“Should an independence be brought about, …we have every opportunity and every encouragement before us, to form the noblest, purist constitution on the face of the earth. We have it in our power to begin the world over again”.

Even as Common Sense became a best-seller in the colonies, Paine refused any royalties so that costs were kept down and the pages were easily affordable to the reading public; which had a high reading rate in America, giving great popularity to newspapers and such pamphlets as Paine and others produced.

In fact, a pamphlet printed the summer before by Pennsylvanian John Dickinson had addressed some of these same issues as A Farmer and included his assessment of what representation should represent; but he had not the flair or the skill of rhetoric that Paine’s epistle achieved.

So popular did Common Sense and later revolutionary writings become, that his critic John Adams would declare sarcastically that the "Age of Revolution" ought to be called the: "Age of Paine." The success drew the author into a whirlwind of appearances and introductions to those men who would become the movers and shakers of the American Revolution.

Nonetheless, when the British took control of New York, Thomas Paine enlisted in the Pennsylvania Associators, a.k.a. General Roberdeau’s "Flying Camp," a volunteer regiment that was called into action when needed. Their first assignment was to march to Amboy, New Jersey, where it was rumored that the British would be landing soon. It was a fruitless march, but when they did spy the Redcoats landing on Staten Island, many were overwhelmed by the number, and the Flying Camp disbanded.

With his military unit broken up, Paine traveled cautiously north to Fort Lee, where he met commander General Nathanael Greene. The General took him in as an aide-de-camp and appointed him Brigadier. The two men took an instant liking to one another, as the General's biographer Ged Carbone notes, "some of Paine's arguments could have come from Greene's pen…".

By all accounts, Paine fared better by the pen than by the sword. He was an ungainly soldier, often the butt of jokes from his fellow enlistees, including one occasion in which his boots and wig were hidden just before an alarm was raised in the middle of the night with the brigade assembled to watch the great philosopher stumble half-dressed from his tent.[xiii]

Still, while in camp, he wrote of the American efforts in the Philadelphia newspapers. By December, however, senior officers had taken him aside and convinced Paine that the words produced by his pen and correspondence would serve the country better than he could as a soldier. Paine agreed and walked thirty-five miles to Philadelphia, expecting to be captured at any moment. Once there, he found the city in chaos, with half the population having fled and the morale of its citizens at a low ebb after news of American defeats.

Paine set out to alter this at once and to restore faith in the American cause. He began writing a series of what would be thirteen essays, one in honor of each colony, that addressed directly with its title: The American Crisis. As his biographer attests, the collected essays “rallied his countrymen,” and with his first, “ennobled each and every citizen rebel into a heroic agent of destiny.”[xiv]

The first Crisis was published a week before Christmas in the Pennsylvania Journal. Printers in the city soon had 18,000 copies of the author's work on the street. Other printers soon put the work to the presses in other colonies. One of these many copies made its way to the Commander-in-Chief-perhaps Paine had sent a copy himself to General Washington, whom he ardently admired as both a person and a soldier.

Washington would gather his troops on the bank of the Delaware River to read Paine's words aloud to them two nights before the planned surprise attack on the Hessian-held New Jersey towns of Trenton and Princeton.

Paine's words stir us today in times of crisis and evoke in us the same resolve that it did that night to the troops gathered there:

“These are the times that try men’s souls. The summer patriot and the sunshine patriot will, in this crisis, shrink from the service of their country; but he that stands it now, deserves the love and thanks of man and woman. Tyranny, like hell, is not easily conquered; yet we have this consolation with us, that the harder the conflict, the more glorious the triumph. What we obtain too cheap, we esteem too lightly: it is dearness only that gives everything its value…”[xv]

The resultant victories on Christmas night and the following day bolstered the morale tremendously, and Congress recognized Paine's value, appointing him secretary to the United States Council of Safety, negotiating a treaty with the Iroquois from late January through March. Then, by John Adam's nomination, Congress appointed him to be secretary for the Committee of Foreign Affairs (formerly the Committee of Secret Correspondence), under whose title he spent ten months wandering back roads on various missions, obtaining information for General Greene and the Pennsylvania Assembly.

For Major-General Nathanael Greene the years 1778-1779 were ones of great upheaval but also of great reward. He began the year at Valley Forge with General Washington and other officers of the Continental Army. He remained with them as they marched to White Plains, New York, where Greene resumed his post as Quartermaster General.

As the spring stretched into summer, considerably more of his time was engaged in gathering supplies for the growing army that General John Sullivan would utilize to wrest Rhode Island, or Aquidneck Island as we know it today, from the British occupiers who had seized the island nearly two years before.

Greene, of course, grew anxious to return to Rhode Island and take part in this effort. He had lobbied early on after the British invasion for a retaliatory strike. Moreover, his wife, Caty, was pregnant at home. He wrote to Sullivan enthusiastically

“I was an adviser to this expedition and therefore am deeply interested in the event….I wish a little more force had been sent…Everything depends almost on the success of this expedition. Your friends are anxious, your Enemies are watching, I CHARGE YOU TO BE VICTORIOUS”.

He complained to merchant Henry Marchant that “it has been going on five years since I have spent an hour at home”, and must have urged Washington at every opportunity to let him go, because in mid- July, the General finally relented, writing to Congress that he

“judged it advisable to send Gen. Greene …being fully persuaded his services, as well as in the Quartermaster line as in the field, would be of material importance in the expedition against the Enemy in that quarter. He is intimately acquainted with the whole of the Country, and besides he has extensive interest and influence upon it.”[xvi]

Greene left White Plains on July 28th and rode two nights and three days to reach his wife in Coventry, where he visited briefly with her and one-year-old daughter Martha; before heading on to Newport, where he arrived in time to see that the fleet from our new French allies had arrived and was anchored off Block Island.

General Greene was assigned command of roughly half the troops that would take the field. He marched his troops from Providence to Tiverton on August 4th. The Marquis de Lafayette followed a day later, giving them a combined 10,000 troops. An additional 4,000 French marines awaited the signal command on Jamestown, an island close by the western side of Aquidneck.

Americans knew that the British garrison held less than 7,000 men. Chances looked good for the Americans to force the British to evacuate Rhode Island.

However,… as with the previous year’s efforts to undertake a like expedition, the combined challenges of gathering an adequate force, especially untrained and inexperienced militia: Lafayette’s aide de camp laughingly wrote that it looked as though the Americans had sent “all the tailors and apothecaries” to take up arms against the British.

The plan was for American troops to cross the Sakonnet River or East Passage to the Island, where they would combine with the French marines for the assault on land while the French fleet would bombard the fortifications the British had erected on the island.

Sadly, the expedition began with a pause, Sullivan writing to the French Commander on the early morning of August 9th, the day of the planned assault, that he needed another day to train his "Motley and disarranged Chaos of militia" in the proper method of boat boarding.

When word came, however, that the British had abandoned a redoubt close to the Sakonnet, the American General rushed 2,000 troops across the river to take the fort at Butts Hill.

An ensuing three-day hurricane-like storm and damage to the French fleet caused the delay and then the eventual abandonment of the expedition. The resultant "Battle of Rhode Island" then was, in actuality, a necessary retreat from the Island.

Greene would command roughly half the troops in the field the day of August 29th, some fifteen hundred men stationed on the west side of the Island. The day began early, with Greene taking his breakfast in a nearby Quaker household to the sound of musket fire from the area of the windmill on Quaker hill.

In the ensuing battle, Hessians attacked the American right flank, which included the 1st Rhode Island, or "Black Regiment," as well as a regiment under Capt. Israel Arnold, and a contingent of Massachusetts troops. The flank withstood the three Hessian drives to dislodge the men from around the redoubt and finally drove them from the field. Greene would write his wife a letter from his saddle late that afternoon:

“We have had a considerable action today; we have beat the enemy off the ground where they advanced upon us; the killed and wounded on both sides unknown, but they were considerable for the number of troops we had engaged…”[xvii]

In the aftermath of the Battle of Rhode Island, Greene urgently hoped to remain in the state and see to his pregnant wife. Caty had tried to stay at the encampment in Tiverton, but the stifling heat in the midst of her condition had sent her home to Coventry. While there, he received a letter from General Washington appointing him a de-facto diplomat and mediator between the French and American officers with whom a potentially serious rift had developed:

"I depend upon your temper and influence to conciliate that animosity," Washington wrote, "…the Marquis (de Lafayette) speaks kindly of a letter from you to him on this subject. He will therefore take any advice from you in a friendly light, and if he can be pacified, the other French Gentlemen will of course be satisfied…"

Major-General Greene duly rode the eighty miles to Boston on horseback and entertained the French officers in the elegant home of John Hancock. He reported back to Washington ten days after his arrival that the Officers in question were now "upon exceeding good footing with the Gentlemen (officers) of the town" and assured the Commander-in-Chief that General Hancock himself was doing all he could "to promote a good understanding with the French officers. His house is full from morning till Night…".

On September 23rd, Greene set off for home, his mission completed, and arrived in a drenching rain-storm to find his wife had given birth to a daughter but was now gravely ill.

Ge. John Sullivan appealed to Washington to let Greene remain in Coventry over the winter. Sullivan still had 3,500 troops in Rhode Island and had come to rely upon the Major-General’s support and counsel.

Within the week, however, Greene had asserted his own desire to return to camp, writing:

"however agreeable it is to be near my family and among my Friends, I cannot wish it to take place, as it would be unfriendly to the business of my department…"

Greene spent the winter traveling from the encampment at Middlebrook to Trenton and Philadelphia, Caty often traveling with a servant and ensconced in stately homes nearby the encampments.

He would spend much of the year of 1779 engaged in supplying the American attack on the Seneca Indian nation, part of Greene’s proposed plan to ransack the stores of the indigenous allies of the enemy.

By October, Greene was stationed on the Hudson River when he received a message from Col. Ephraim Bowen in Rhode Island. It was exceedingly good news as both a Rhode Islander and as Quartermaster General, for Bowen wrote:

“I have the Pleasure to Acquaint you of the Evacuation of this Island by the British Army on Monday night last…The Enemy have left about Fourteen hundred Tons of Excellent Hay, Sixty of (or) Seventy Tons of Straw, (and) upwards of three hundred Cords of Wood."

As the harsh winter of 1779-1780 was fast approaching, Bowen added a footnote for his friend:

"I will get you a pair of English blankets."

Coming from a man who was an unmistakable genius in calculating the political needs and wishes of his reading audience, it seemed the plan of a madman. Thomas Paine had labored away at his American Crisis series, all while still serving as clerk to Pennsylvania’s Assembly. He had been instrumental in the Assembly’s abolishment of slavery on March 1, 1780, and been given an honorary degree from the University of Pennsylvania on the 4th of July.

Now, Paine devised a plan in which he would take a year's leave and go to England incognito to produce a scathing pamphlet that would stir unease among the people with their King. He wrote to Nathanael Greene of his plans on September 9, 1780:

“The manner in which I would bring such a publication out would be under the cover of an Englishman who had made the tour of America incognito. This wil afford me all the foundation I wish for and enable me to place matters before them in a light in which they had never yet viewed them…”

Greene was so concerned by this letter that he rode to Paine’s rooming house in Philadelphia to dissuade him of the adventure. Having spent the past weeks engaged in overseeing the conspiracy trial of British officer John Andre and conspirator with the American traitor Benedict Arnold, he could give sure advice to Paine on the consequences of being found among the enemy. Paine wisely took his advice and dropped the idea.

It was the last time the two friends would see each other in person. Greene was called away almost at once to command the American army in the southern campaign. Congress drafted Paine in the coming months to write to the French minister, asking for another loan of one million pounds. He would later take the job of secretary to Col. John Laurens, who at twenty-six had been appointed Congress' new emissary to France.

Their arrival, however, was an unhappy occasion, with the aging Benjamin Franklin disheartened by the news of his replacement, so upset that he resigned from Congress, though the body refused his request. Paine returned from France with another successful mission under his belt, and his return to Philadelphia was bolstered by jubilant crowds in the wake of America’s victory, raising toasts across the town to the fireworks that lit the night skies.

He soon felt dejected, however, as many veterans do after their return. Paine felt the country had let him down. In his poverty after the war, he became embittered as he saw others who had become rich off the conflict, he himself had often given his entire royalties and even salaries to the support of the Army. He wrote to the friend he knew would support him and hopefully influence Congress to support him financially. As Paine knew he would, Greene wrote a letter of support:

“I have always been in hopes that Congress would have made some handsome acknowledgements to you for past services. I must confess that I think you have been shamefully neglected; and that America is indebted to few characters more than to you. But as your passion leads to fame, and not to wealth, your mortifications will be the less. Your fame for your writings will be immortal. At present, my expenses are great; nevertheless, if you are not conveniently situated, I shall take a pride and pleasure in contributing all in my power to render your situation happy”.

This was the last letter Paine was to receive from his friend.

General Nathanael Greene did indeed have great expenses, and his efforts to retrieve funds swindled from him by shady creditors during the war surely led to his untimely death in 1786 at the age of forty-four.

We can only speculate on the influence Nathanael Greene would have held had he lived long enough to be part of the nation's first administration. His pragmatic approach to situations and his learning and hard-earned experience would have certainly made him a valuable asset to President Washington.

In these formative and often turbulent years of the nation’s childhood, Greene would likely have effectively grounded Jefferson’s flights of fancy about democracy becoming a world movement of peaceful takeovers from monarchy. He might also have tempered John Adam’s authoritative tendencies.

Thomas Paine would go on to write what is arguably his most remarkable work in The Rights of Man, in which a proclamation echoes those of his correspondence with General Nathanael Greene and the cause they shared together:

“…individuals themselves, each in his own personal and sovereign right, entered into a compact with each other to produce a government: and this is the only mode in which governments have a right to arise, and the only principle on which they have a right to exist.”[xviii]

[i] Nelson, Craig Thomas Paine: Enlightenment, Revolution, and the Birth of Modern Nations New York, Viking 2006 p. 14

[ii] Dexter, ed. The Literary Diary of Ezra Stiles D.D. L.L.D. Charles Scribners Sons, 1901 Vol. 1 p.213

[iii] Enough of a gentleman that he could entertain Martha Washington in conversation at Valley Forge while his wife and her husband danced into the small hours of the morning.

[iv] Nelson, Craig Thomas Paine p. 49

[v] Carbone, Gerald Nathanael Greene, A Biography of the American Revolution New York, Macmillan 2008 pp 21-23

[vi] Ibid. p. 25

[vii] Thayer, Theodore Nathanael Greene: Strategist of the American Revolution New York, Twayne Publishers 1960 p. 72

[viii] Ibid. p. 78

[ix] Nelson, p.60

[x] Ibid. p. 64

[xi] Ibid. p. 77

[xii] Wood, Gordon Power and Liberty: Constitutionalism in the American Revolution New York, Oxford University Press, 2019 p. 30

[xiii] Nelson, pp. 103-104

[xiv] Ibid. p. 107

[xv] Ibid. p. 108

[xvi] Carbone, p. 99

[xvii] Ibid, p. 112

[xviii] Nelson, p. 201